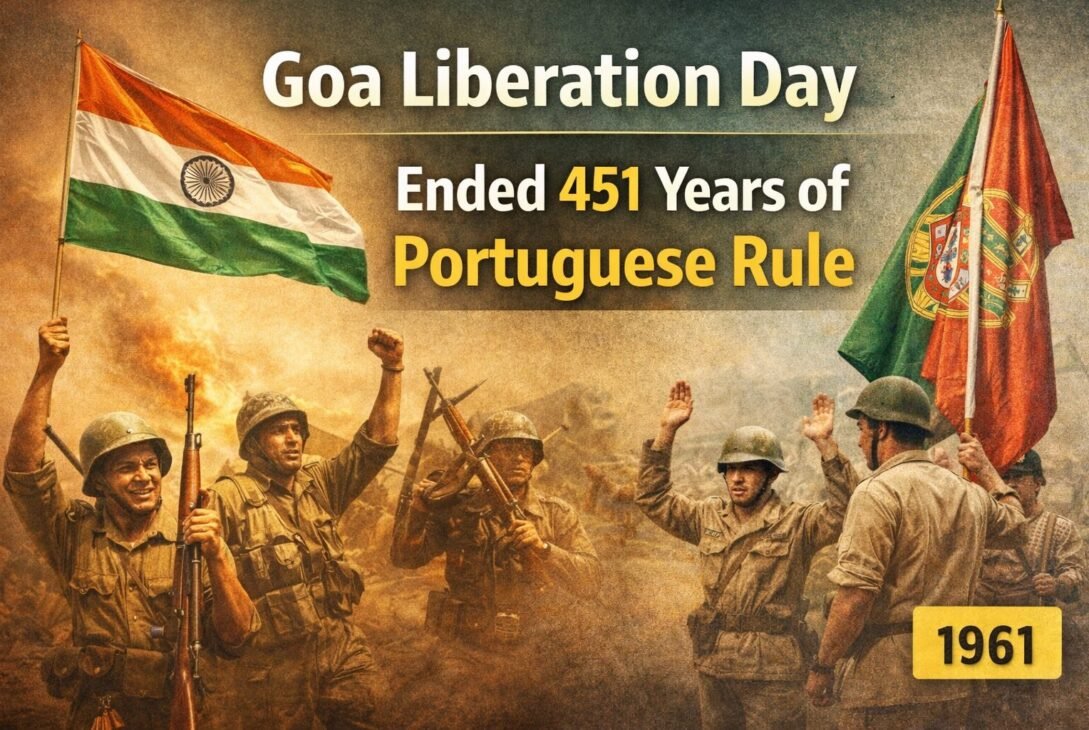

In 1947, the tricolour rose across India. Millions celebrated freedom from colonial rule. But in one corner of the subcontinent, there was no celebration — because there was no freedom. Goa, today one of India’s most beloved tourist destinations, remained under Portuguese control for another fourteen years after independence. It took a military operation, decades of failed diplomacy, mass revolts, and a 36-hour war before Goa Liberation Day finally became a reality on 19 December 1961.

You might wonder why. If Britain left, and France eventually surrendered Pondicherry, why did Portugal cling to Goa so stubbornly? And why did India — a newly independent nation with a massive military advantage — wait so long to act?

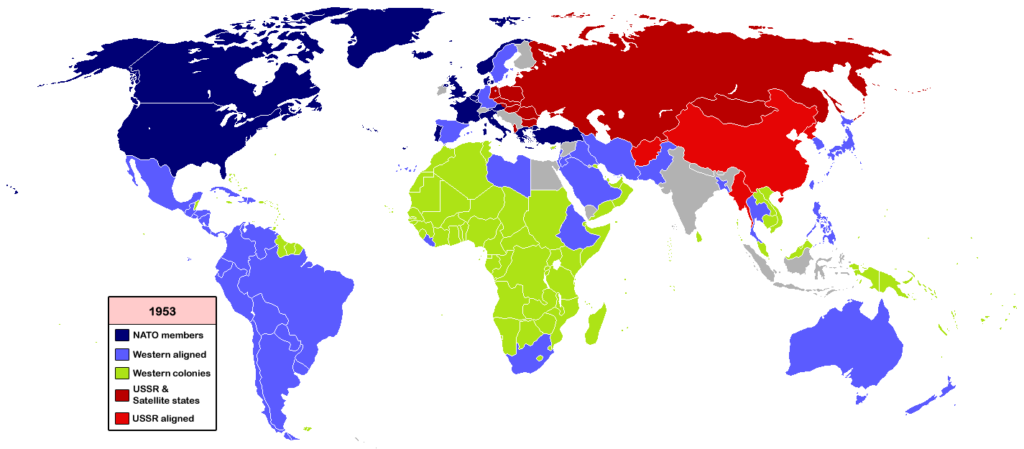

The answers involve Cold War politics, NATO alliances, centuries of cultural transformation, and a dictator in Lisbon who refused to accept that colonialism was over. This is the full story behind Goa Liberation Day — from the first Portuguese ships to the final instrument of surrender.

Before the Portuguese: Goa’s Ancient Roots

Understanding the history of Goa means going back much further than European colonialism. This was never an empty land waiting to be “discovered.” It was one of the earliest regions of human settlement in India, referenced in Hindu Puranas and various inscriptions under the names Sindhapur and Sandha.

By 250 BC, Goa was part of the Mauryan Empire. The Bhoja Kings controlled it from roughly 300 AD to 600 AD, and the Kadamba Dynasty held power from the second century CE until 1312. Then came the Deccan’s Muslim invaders, who made Goa their base from 1312 to 1367. The Vijayanagara Kingdom annexed it next, only to lose it to the Bahmani Sultanate.

Here’s the thing about Goa — it was always contested. Its strategic harbour made it one of the most fought-over ports in western India. The Bahmani and Vijayanagara empires treated it as a prize to be won and re-won. That tug of war eventually opened the door for an outsider.

In 1492, Yusuf Adil Shah, the governor of Bijapur, broke away from the Bahmani Kingdom and seized Goa. But his rule brought no peace. Historians broadly agree that Hindu communities faced severe oppression under Adil Shah’s administration, and the local population grew desperate enough to seek help from an unlikely source — the Portuguese.

How Portugal Planted Its Flag: The Fall of Adil Shah

A local Goan named Timayya allied himself with Afonso de Albuquerque, a Portuguese general and the Viceroy of Portuguese India. Together, they hatched a plan to overthrow Yusuf Adil Shah. The first attempt failed. The second did not.

Albuquerque defeated Adil Shah decisively. But then came the betrayal that would reshape Goa for the next four and a half centuries. Timayya had assumed the Portuguese would establish a trading post and leave governance to the locals. Instead, Albuquerque stayed. He consolidated control, and Portuguese settlers began arriving in waves — farmers, retail traders, artisans — many of whom married local women and established a privileged Eurasian community.

This pattern — a local population inviting external help against one oppressor, only to gain a new one — plays out repeatedly across colonial history. What makes Goa’s case unique is the sheer duration. Most colonial occupations lasted a century or two. Portugal held Goa for 451 years.

Adil Shah tried to recapture Goa three months later. He failed again and died the same year. By 1510, Goa was firmly under Portuguese control, and the transformation of the region had begun.

Why Portugal Chose Goa

Portugal didn’t stumble onto Goa by accident. Vasco da Gama had opened Asia’s doors for Western Europe, and the Portuguese were actively seeking a strong naval base to protect their Indian Ocean trade routes. Goa offered exactly that — an excellent harbour, favorable sailing conditions, and a strategic location for controlling the spice trade.

But trade was only part of the equation. Everywhere the Portuguese established settlements, they used religious policy as a tool of political control. In Goa, this meant aggressive promotion of Christianity. Forced conversions became widespread—those who refused faced severe punishments. Temples were demolished and replaced with churches — including structures like the Basilica of Bom Jesus, Se Cathedral, Church of St. Francis of Assisi, and Fort Aguada, many of which still stand today as part of old Goa church history.

Portuguese language, education, and customs were imposed on the population. Over time, religious intolerance escalated. Hindu temples, marriages, and cremations were banned outright. The Western influence became so pervasive that the Portuguese themselves boasted that if you’d seen Goa, you didn’t need to visit Lisbon. Saint Francis Xavier compared the city’s architecture to the Portuguese capital as early as 1542.

By the 16th century, Goa’s markets were filled with Bahraini pearls and coral, Chinese porcelain and silk, Portuguese velvet and Finnish textiles, and expensive medicines. Portugal had reached the apex of its power in India. But that power was about to face challenges — from the Dutch, from the British, and eventually, from the Goans themselves.

Centuries of Resistance: Goa’s Forgotten Revolts

Most people associate India’s freedom struggle exclusively with the fight against Britain. But Goa’s first revolt against colonial rule happened in 1555 — more than 300 years before the Revolt of 1857. The local population had grown exhausted by Catholic priests’ oppression and exorbitant land revenue demands. The Portuguese crushed this uprising brutally, and Goa fell silent for a long time.

The next major eruption came in 1787 — the Pinto Revolt, also known as the Pinto Conspiracy. Its root cause was structural discrimination: the Portuguese appointed European clergy to senior church positions while sidelining local Goan Catholic priests. The local priests rebelled. The Portuguese crushed that revolt, too, and executed everyone involved.

Then came the Ranes of Satari, a family that challenged Portuguese authority for nearly 150 years. The last member of this resistance, Dada Rane, launched guerrilla warfare against the Portuguese alongside his companions. Once again, the revolt was suppressed. This time, Dada Rane and his allies were deported to an island in the Pacific Ocean.

What’s striking about this pattern isn’t the revolts themselves — it’s the Portuguese response. Every rebellion was met with overwhelming force, followed by periods of enforced silence. The resistance never truly died; it was simply driven underground, waiting for the right moment to resurface.

The 20th Century Awakening

That moment arrived in the 20th century, as India’s broader freedom movement gained momentum. A French-educated Goan engineer named Tristão de Bragança Cunha raised his voice against Portuguese atrocities, and in 1928, the Goa Congress Committee was formed. Its roots were connected to the Indian National Congress.

Mass movements erupted across Goa. The Portuguese responded with arrests and police firings. But the protests didn’t stop. Non-violent demonstrations ran parallel to armed attacks by groups like the Azad Gomantak Dal and the United Front of Goans.

Yet none of it was enough to dislodge Portugal. And during this entire period, India’s biggest leaders — from Mahatma Gandhi to Sardar Patel — were consumed by the fight against Britain. Goa simply wasn’t their primary focus.

That changed in 1946 when Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia launched his agitation in Goa. Lohia’s involvement electrified the Goan youth, and thousands joined the liberation battle. But the Portuguese cracked down hard. Lohia and several other leaders were arrested. Many were jailed; others were exiled to Angola and Cabo Verde. By 1947, the movement had been temporarily silenced.

Source: The Quint

Why Goa Missed 1947: The Independence India Couldn’t Complete

India became independent on 15 August 1947. France eventually handed over Pondicherry in 1954 without a fight. But Portugal refused to leave Goa.

Their argument was audacious: Goa wasn’t a colony, they claimed — it was an integral part of Portugal itself. Portuguese Prime Minister António de Oliveira Salazar told India in plain terms that since Portugal had “settled” Goa long before the Republic of India existed, Goa couldn’t possibly be Indian territory. When India invited diplomatic negotiations in February 1950, Portugal refused outright.

You might ask why Pakistan never claimed Goa the way it claimed Kashmir or Junagadh. The answer lies in demographics and politics. Goa’s population had a strong Christian influence thanks to centuries of Portuguese conversion campaigns, which didn’t align with Pakistan’s claims based on Muslim-majority populations. Besides, Goa was already under Portuguese control, and Pakistan couldn’t afford to fight both India and Portugal simultaneously.

India responded to Portugal’s stubbornness with escalating pressure. In 1953, India withdrew its diplomatic mission from Lisbon. In 1954, the government imposed visa restrictions between Goa and the rest of India, cutting off Portuguese freedom of movement. Economic sanctions followed, blocking the Portuguese from trading with other Indian states.

The Dadra and Nagar Haveli Breakthrough

These sanctions emboldened Goa’s freedom fighters. In 1954, armed revolutionaries liberated Dadra and Nagar Haveli from Portuguese police — a stinging defeat for Lisbon. Inspired by this victory, thousands of unarmed activists attempted to enter Goa in 1955. The Portuguese response was horrifying: they opened fire on the crowd, killing and injuring many. Most of these protesters belonged to the Vimochana Samiti and the Indian National Congress (Goa).

This massacre forced India to shut its consulate in Goa. Nehru had believed satyagraha could free Goa the way it had freed India from Britain. That belief was now crumbling.

So why didn’t Nehru just send the army, the way India had annexed Hyderabad? One word: NATO. Portugal was a NATO member. If India attacked Portuguese territory, there was a real possibility that NATO and the United States would intervene on Portugal’s side. This wasn’t a hypothetical risk — it was a genuine geopolitical constraint that kept India’s hands tied for years.

Operation Vijay 1961: 36 Hours That Changed Everything

The tipping point came when the Portuguese fired on the Sabarmati, an Indian passenger boat, killing several Indian civilians for no provocation. Jawaharlal Nehru decided that the time for table talks was over.

In August 1961, India formally annexed Dadra and Nagar Haveli. Portugal still refused to budge on Goa. But the Portuguese knew what was coming — they evacuated their women and children back to Portugal while the men stayed behind to defend the territory.

On 17 December 1961, in the early hours, India launched Operation Vijay 1961. The army, navy, and air force surrounded Goa from all sides. The Portuguese were vastly outnumbered. Salazar had ordered his forces to fight to the death, and if that failed, to implement a scorched earth policy — destroying everything that could be useful to the enemy.

But the Portuguese Governor General, Manuel António Vassalo e Silva, looked at the reality on the ground. Thirty thousand Indian troops were closing in. No reinforcements were coming from Portugal — the Suez Canal crisis had effectively sealed off the sea route, and Egypt had closed the canal to most Western nations. Fighting was futile. Surrender was the only option that saved lives.

By the evening of 18 December, Indian soldiers had liberated most of Goa. Within just 36 hours, the operation was complete. On 19 December, both sides signed the Instrument of Surrender, formally ending 451 years of Portuguese rule in Goa.

That date — 19 December — is now celebrated as Goa Liberation Day every year.

After Liberation: A Divided World Reacts

Goa’s reaction to liberation was mixed. For many, it was a moment of long-awaited joy. For others who had spent their entire lives under Portuguese cultural influence, it brought uncertainty.

Portugal severed all diplomatic ties with India and refused to recognize Goa as Indian territory. The loss hit Lisbon so hard that Christmas celebrations were replaced with mourning that year — no lights, no festivities.

The international reaction split along Cold War lines. The Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Arab States, Ghana, Indonesia, and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) supported India’s action. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev wrote to Nehru describing India’s steps as entirely lawful and justified. The United States, the United Kingdom, NATO members, France, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Spain, West Germany, and Pakistan all criticized India’s move.

After a period of military rule, Goa held elections in 1962, and Dayanand Balkrishna Bandodkar became its first Chief Minister.

Consider what this moment meant for Goa’s identity. A territory that had been under Portuguese control since before Columbus reached the Americas was suddenly part of a democratic republic less than fifteen years old. The cultural whiplash was immense — and its echoes are still visible in Goa’s unique blend of Indian and European character today.

Why Goa Liberation Day Still Matters

Today, Goa celebrates two independence days. On 15 August, it joins the rest of India in marking freedom from colonial rule. On 19 December, it celebrates Goa Liberation Day — the date that actually gave its people that freedom.

The story of how Goa was liberated from the Portuguese is not just a military footnote. It’s a lesson in how colonial powers justify occupation, how Cold War alliances can protect oppressors, and how the gap between a nation’s independence on paper and the liberation of all its people can stretch across decades.

For anyone searching for the complete picture behind Goa Independence Day, the answer doesn’t begin in 1961 or even 1947. It begins in 1510, with a local man named Timayya who invited a foreign power to help him fight a tyrant — and accidentally handed his homeland to a new one for the next 451 years.