Introduction

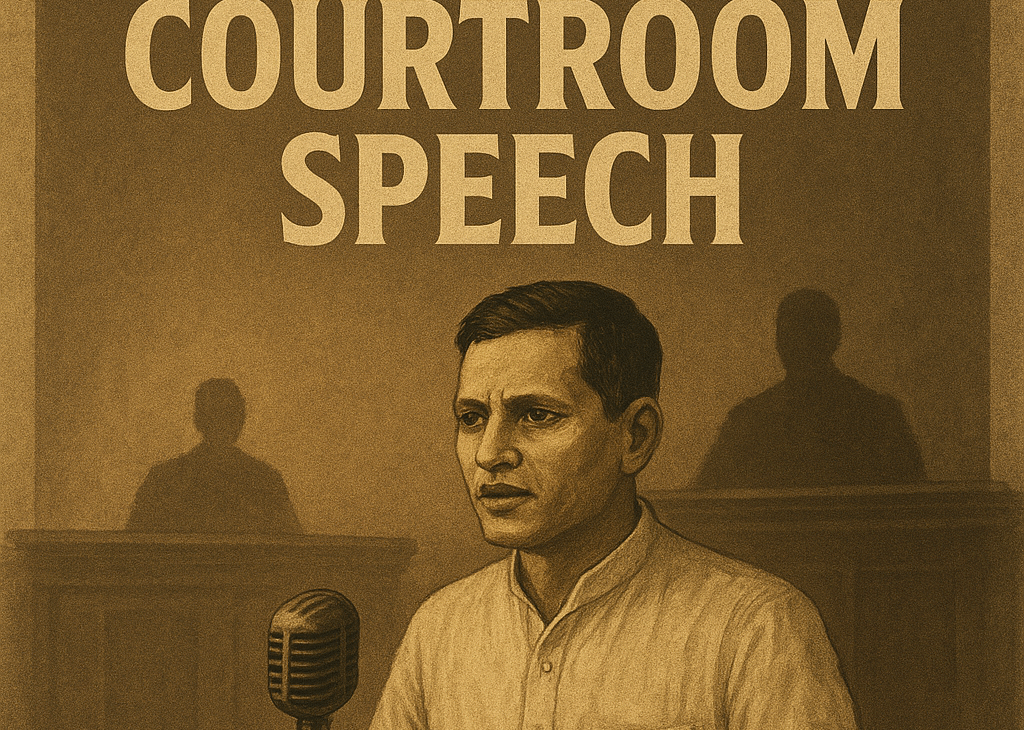

The Nathuram Godse speech delivered during the Gandhi assassination trial remains one of the most controversial courtroom statements in modern Indian history. Spoken not as a spontaneous outburst but as a structured legal and ideological declaration, the speech was intended to explain, justify, and contextualize the actions that culminated on 30 January 1948.

This article reproduces the Nathuram Godse courtroom speech for historical and educational purposes. It does not endorse the views expressed. Instead, it aims to preserve the document as part of India’s legal and political history, allowing readers to critically examine the arguments presented during the trial.

What follows is Godse’s structured statement, addressing procedural objections, conspiracy allegations, evidentiary disputes, ideological motivations, and his final justification.

Misjoinder of Charges and Request for Separate Trials

Godse begins by challenging the legality of the charges. He argues that the prosecution improperly combined two separate incidents—20 January 1948 and 30 January 1948—into a single trial. According to him, this constituted a misjoinder of charges, violating procedural fairness.

He asserts that each incident required an independent trial. By merging them, the prosecution, in his view, compromised the integrity of judicial proceedings and rendered the trial legally defective.

Submission on Charges as Framed

Without conceding his objection, Godse proceeds to address the charges individually. This dual strategy—procedural objection followed by substantive response—forms the legal backbone of the Nathuram Godse court statement.

He emphasizes that responding to the charges does not imply acceptance of their legality.

Overview of the Charge-Sheet

Godse critiques the charge-sheet’s central assumption: that the events of 20 January and 30 January were part of a single conspiracy culminating in Gandhi’s assassination.

He categorically rejects this narrative, asserting that all actions prior to 20 January were independent and unrelated to the final act on 30 January.

Rejection of Conspiracy Allegations

One of the gravest accusations was conspiracy to murder Mahatma Gandhi. Godse denies this completely.

He states there was:

- No agreement

- No collaboration

- No shared criminal objective

among the accused. He further denies aiding or abetting any individual involved in the assassination.

This denial forms a central pillar of the Gandhi assassination trial speech.

Unreliable Evidence and Prosecution Witnesses

Godse directly attacks the credibility of Digambar Ramchandra Badge, the prosecution’s witness no. 57. According to Godse, Badge’s testimony regarding meetings, weapons, and planning was fabricated.

He denies ever meeting Badge at the Hindu Rashtra newspaper office or discussing arms at any point, directly undermining the prosecution’s conspiracy theory.

Denial of Arms and Ammunition Charges

Godse rejects allegations of transporting explosives, pistols, or ammunition on 20 January 1948. He states that he neither possessed nor facilitated the movement of weapons and did not assist anyone else in doing so.

This section attempts to dismantle the logistical foundation of the prosecution’s case.

Explosives and Attempted Murder Charges

Addressing the gun-cotton slab incident at Birla House, Godse denies all involvement. He argues that no credible evidence links him to the explosion or to any attempted murder prior to 30 January.

Abetment and Connection with Murder

Godse also denies abetting the murder of Mahatma Gandhi. He states that he had no connection with Madanlal Pahwa or others accused of prior attempts.

According to him, the prosecution failed to establish any causal or operational link.

Denial of Pistol Procurement

Godse denies procuring an unlicensed pistol with the help of Narayan Apte. Even if such procurement occurred, he argues, jurisdictional and evidentiary gaps render the charge unsustainable.

Acknowledgment of Pistol Possession

In a critical admission, Godse acknowledges possessing an automatic pistol but denies that Apte or Vishnu Karkare assisted him in acquiring it.

This distinction is legally significant within his broader defense strategy.

Motive Behind My Actions

Godse then shifts from legal defense to ideological explanation.

He openly criticizes Mahatma Gandhi’s doctrine of absolute Ahimsa, which he believed weakened Hindu society. He accuses Gandhi of pro-Muslim bias after Partition and claims this harmed Hindu interests.

This ideological section defines the moral framework of the Nathuram Godse ideology.

Formation of Agrani and Hindu Rashtra

To counter Gandhi’s influence, Godse and Apte founded Agrani, later renamed Hindu Rashtra, as a daily newspaper promoting Hindu unity and resistance to Gandhi’s ideas.

He acknowledges receiving support from Veer Savarkar, though he later distances himself from organized leadership.

Relationship with Veer Savarkar

Godse describes working closely with Savarkar but expresses disappointment with the Hindu Mahasabha’s cautious political approach. He believed the leadership failed to respond decisively to what he viewed as anti-Hindu policies.

Disillusionment with Hindu Mahasabha Leadership

As the partition violence intensified, Godse’s dissatisfaction grew. He openly criticized the Mahasabha and chose a more radical, independent path.

Demonstrations Against Gandhiji

Godse recounts participating in peaceful demonstrations in January 1948. He claims that these actions failed to influence Gandhi, leading him to consider more extreme measures.

Final Steps and Acquisition of the Pistol

Godse narrates his journey to Gwalior, his failed meeting with Dr. Parchure, and his eventual purchase of a pistol from a refugee arms dealer. He identifies this weapon as the one used on 30 January 1948.

Reflections on Ideology

In the concluding ideological section, Godse references thinkers such as Vivekananda and Dadabhai Naoroji, claiming his actions stemmed from intellectual conviction rather than personal hatred.

Conclusion

The Nathuram Godse speech stands as a historical document that blends legal argument, ideological reasoning, and personal justification. While the act it defends is universally condemned, the speech itself remains essential for understanding the political and psychological climate of post-Partition India.

Studying this statement allows readers to critically assess how ideology, grievance, and radicalization intersect within history.