Introduction

After the dramatic life sentence following the Central Assembly bombing, Bhagat Singh and his comrades faced a new chapter that would define their immortal legacy — the trial and the gallows. What unfolded next was not merely a courtroom proceeding but a fierce ideological battle between a colonial empire and a generation that refused to bow. From the farcical trials before British magistrates to the hunger strikes that shook an empire, from the draconian Lahore Conspiracy Case Ordinance to the final march toward martyrdom, Bhagat Singh transformed every moment into a weapon of revolution.

The Courtroom as a Political Stage

The trial began on May 7, 1929, before Magistrate Poole, with Asaf Ali volunteering as defense. Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt demanded their statements be recorded before a Sessions Court. The request was granted, and proceedings began before Judge Middleton on June 4, 1929.

During the hearings, Bhagat Singh challenged the very premise of the prosecution. In response to Lord Irwin’s claim that the bombing was an attack on the Constitution, he declared that it was, instead, an act of protest against a sham institution that perpetuated India’s helplessness. His words thundered through the courtroom:

We have studied our country’s history, the present situation, and the ideals of humanity. We despise deceit.

This Assembly has no worth; it is a symbol of an irresponsible and arrogant government’s oppressive power.

When asked to define revolution, Bhagat Singh replied with clarity and conviction:

Revolution does not necessarily mean a violent struggle. There is no place for personal hatred in it.

The bomb and the pistol are not revolution; the real revolution is to replace an unjust system built on exploitation.

Those who produce and labour are the foundation of the economy — yet their rights are stolen by the exploiters.

He ended his statement with the immortal words:

We are ready to sacrifice our lives on the altar of this great cause.

No sacrifice is too great for our ideal.

We await the triumph of revolution with patience.

Inquilab Zindabad!

The trial concluded on June 10, 1929, sentencing both Bhagat Singh and Dutt to life imprisonment.

The Appeal in Lahore High Court: A Defiant Plea

The appeal was heard before Justices Ford and Addison of the Lahore High Court. There, Bhagat Singh delivered a powerful new statement that redefined the meaning of justice and intent:

My Lord, we are neither barristers nor scholars of English. We request you to look beyond grammar and focus on the spirit of our statement… The punishment given to us is excessively severe and reeks of vengeance.

No one can judge an act without understanding its intent. If intent is ignored, even commanders become murderers, tax collectors become thieves, and preachers become liars.

He concluded with unwavering dignity:

We are not here to beg for mercy or a lighter sentence. We are here to make our position clear. The punishment is not what matters — understanding is.

The High Court upheld the life sentence on January 13, 1930, setting the stage for an even greater battle — the Lahore Conspiracy Case.

The Hunger Strikes and the Martyrdom of Jatindra Nath Das

Transferred to the Mianwali Jail, Bhagat Singh and Dutt soon witnessed the brutal treatment of prisoners and began a hunger strike demanding the rights of political prisoners — better food, reading materials, newspapers, clean clothing, and exemption from forced labour.

The protest spread as the British tried to suppress it with violence and forced feeding, but Bhagat Singh’s resolve only deepened as he grew weaker.

On September 13, 1929, his comrade Jatindra Nath Das died after 63 days of hunger strike. Bhagat Singh, pale but composed, remarked:

For now, this is enough. Let us see how far the government implements the recommendations.

Das’s death shook the nation. The entire country mourned, transforming the prison protest into a national awakening.

After 114 days, on October 5, 1929, Bhagat Singh and his comrades ended their fast — not in defeat, but in triumph. The world now saw him as the voice of the oppressed, the unbroken spirit of resistance.

The Farcical Trials and Brutal Repression

The Lahore Conspiracy Case trial began on July 10, 1929. Even in weakness, Bhagat Singh and his comrades entered court singing patriotic songs and shouting Inquilab Zindabad! The sessions soon turned chaotic — especially when one witness, Jai Gopal, who had turned approver, was mocked by the accused. In fury, a revolutionary threw a shoe at him. The British court retaliated brutally, ordering the accused to be handcuffed and beaten.

Eight Pathan policemen pounced upon Bhagat Singh and thrashed him mercilessly.

The next day, the prisoners refused to attend court, declaring, “We will not go, even if it means death.”

News of the brutality sparked outrage across India and abroad. Protest meetings and condemnations poured in, forcing the government to resume the trial more cautiously.

Leaders like Subhas Chandra Bose, K.F. Nariman, Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, and Baba Gurudutt Singh attended the court to show solidarity with the revolutionaries.

The Lahore Conspiracy Case Ordinance

In May 1930, Governor-General Lord Irwin issued a special decree — the Lahore Conspiracy Case Ordinance — allowing trials in the absence of defendants, witnesses, or lawyers. A special tribunal was formed under Justice J. Coldstream, with Justice Agha Haider and Justice G.C. Hilton as members.

When Bhagat Singh and his comrades appeared before the tribunal, they once again used the courtroom as a stage for defiance — singing patriotic songs and chanting slogans. The British judges fumed, but Agha Haider remained calm. When the accused were beaten inside the court on May 12, 1930, Agha Haider rose in protest and refused to sign the record:

“I am not a party to the order that led to today’s violence.”,

he wrote — a rare act of conscience under imperial rule.

Agha Haider was promptly removed from the bench. The new tribunal — with Justice Elson, Justice Abdul Qadir, and Justice J.K. Topp — continued the trial in their absence, completing it on August 26, 1930.

The Verdict: Death and Defiance

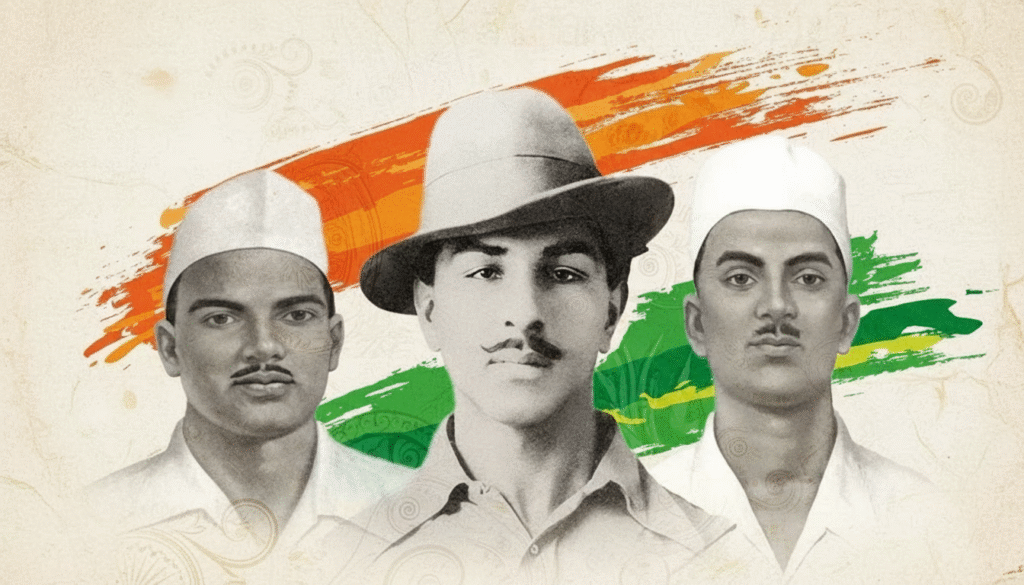

On October 7, 1930, the tribunal pronounced its verdict — not in open court, but inside the Lahore Jail. The 68-page judgment sentenced Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru to death by hanging. Others received life or lesser sentences.

The news leaked despite government censorship. By October 8, the entire nation was ablaze with outrage. Students boycotted classes, women led protests, and rallies filled the streets. Yet, by December 1930, it was clear that the British were determined to execute Bhagat Singh.

The Father’s Plea and the Son’s Letter

Desperate, Bhagat Singh’s father, Kishan Singh, submitted a mercy petition to the Viceroy, arguing his son’s innocence. When Bhagat learned of it, his pain turned to indignation. His letter to his father remains one of the most powerful declarations of revolutionary integrity:

I was shocked to hear you have filed a mercy petition. You had no right to do so without my consent.

My life is not as precious as you believe. To save it at the cost of my ideals would be the real death.

We are all under a moral test, Father — and I must say, you have failed this one.

Ironically, Kishan Singh later ensured this letter was published across newspapers, amplifying his son’s voice even in disagreement.

The Final Days and the Embrace of Martyrdom

As appeals were made to the Privy Council, Bhagat Singh agreed — not out of hope for clemency, but to buy time. He wanted his execution to coincide with the height of public unrest so that his death could ignite a revolution.

If our execution is delayed, it will be unfortunate,” he told his comrade Vijay Kumar Sinha.

For revolution to succeed, our sacrifice must come at the right moment.

The Privy Council rejected the appeal in November 1930. Even as the Gandhi-Irwin Pact in February 1931 released most political prisoners, Gandhi refused to intervene in cases involving violence. Bhagat Singh respected his ideological difference but stood firm in his own path.

By March 1931, the end was near. Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru faced death with unflinching calm. On the eve of their execution, they joked with the guards, sang songs of freedom, and refused the blindfold.

At dawn, their voices echoed one last time through the Lahore Jail:

Down with Imperialism!

Long Live the Revolution!

Inquilab Zindabad!

Conclusion

Bhagat Singh’s trial was more than a legal proceeding; it was the moral trial of an empire. From the courtroom to the gallows, he remained unbroken — his mind sharper than the hangman’s noose, his faith stronger than British steel. His death on March 23, 1931, turned him into an immortal symbol — a martyr whose ideals of justice, equality, and fearless defiance continue to inspire India’s conscience.