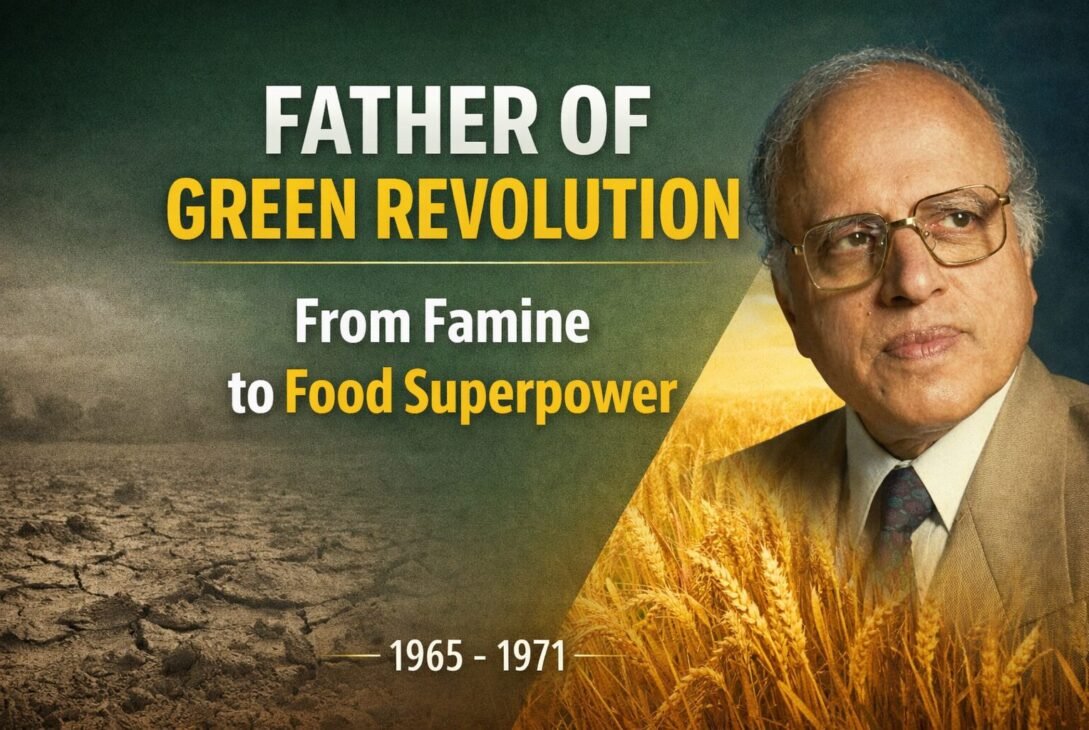

On 13 May 2022, India banned wheat exports. Global wheat prices surged almost overnight. Markets already reeling from the Russia-Ukraine war now faced an even deeper supply crisis, and countries, including the United States, urged India to reverse the decision. But here’s the part most people miss — that a country could shake global food markets with a single policy decision would have been unthinkable just decades earlier. This is the story of how the father of the Green Revolution in India, MS Swaminathan, along with a handful of scientists, politicians, and millions of farmers, pulled a starving nation off its knees and turned it into the world’s second-largest wheat producer.

To understand why India banned wheat exports with such confidence, you need to understand where the country came from. And that story begins not with triumph, but with hunger, humiliation, and a dependence on American charity that came with strings attached.

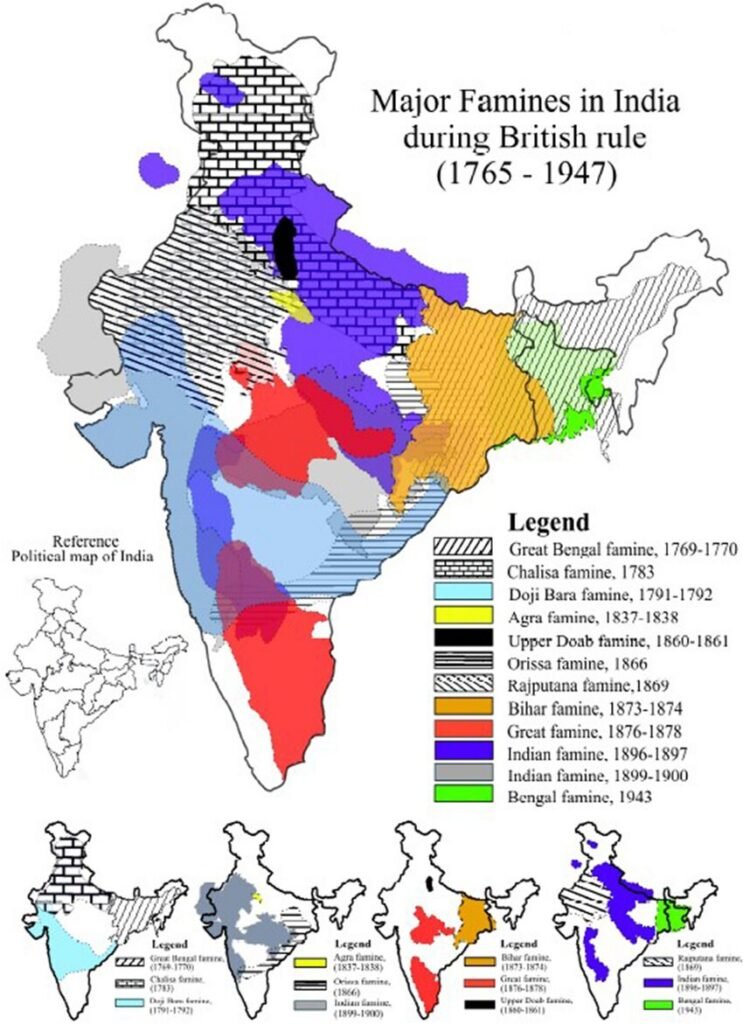

The Hunger That Shaped a Nation

Two hundred years of British colonial rule left India hollowed out. A country once called “the golden bird” couldn’t feed a large portion of its own people. The worst devastation hit Bengal between 1943 and 1944, when famine killed over 3 million people, not because food didn’t exist in the world, but because it didn’t reach them.

When the British left in 1947, they left behind a devastated agricultural sector. Consider what India was working with: over 70% of the population depended on farming, yet only about 10% of agricultural land had access to irrigation. The entire sector ran on the monsoon’s mercy. Between 1950 and 1951, India produced just 50 million tons of food grains — nowhere near enough for a population of 350 million.

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru understood the stakes clearly. His view was straightforward: hungry people cannot build a great nation. The First Five-Year Plan prioritized agriculture, the government built dams and began subsidizing fertilizers, and growth rates climbed from zero to about 3%. But it still wasn’t enough.

Here’s where a strategic miscalculation made things worse. The next Five-Year Plan shifted focus from agriculture to industrialization. Western nations were racing ahead on the back of industrial output, and India needed factories alongside farms. The logic was sound. The timing was terrible. Agricultural growth stalled again, and India started importing food grains to cover the shortage.

Then came the 1962 war with China, which drained resources and set development back by years. Two years later, a devastating drought pushed a third of the population toward starvation. And in the middle of this crisis, in 1964, Prime Minister Nehru passed away.

America’s PL 480 Scheme: Food Aid or Political Weapon?

Lal Bahadur Shastri became the next Prime Minister, inheriting a country fighting famine and war simultaneously. To understand the pressure he faced, you need to know about the PL 480 scheme — the American program that fed India but also kept it on a leash.

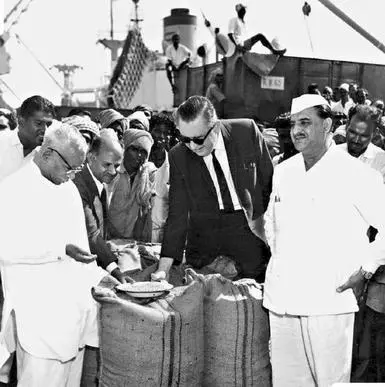

In 1954, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower launched Public Law 480, a program to ship surplus American food to deficit countries at reduced prices. The US branded it “Food for Peace,” projecting an image of generosity. The reality was more transactional. India paid for the grain in Indian rupees, which America could only reinvest within India. Washington also required India to purchase pesticides and fertilizers from American companies. Both sides got something — but the leverage was entirely one-sided.

Between August 1956 and November 1959, India imported roughly 10.5 million metric tons of grain under this arrangement. When Eisenhower visited India in 1959 and met Nehru, he promised continued food support with payment in Indian currency. By 1960, the wheat shipments quadrupled.

But the quality of American wheat told a different story. Some experts considered it fit only for animal feed. Despite public criticism of the government for buying such poor-quality grain, India had no alternative. The monsoons had been unreliable, wheat production had declined sharply, and by 1964, American agricultural experts visiting India predicted that the country was heading toward a famine in the 1970s that could kill millions.

One way to read the PL 480 arrangement is as a classic Cold War strategy dressed up as humanitarianism. America wanted to keep India from drifting toward the Soviet Union, and food dependency was a convenient pressure point. This wasn’t just aid — it was geopolitical positioning.

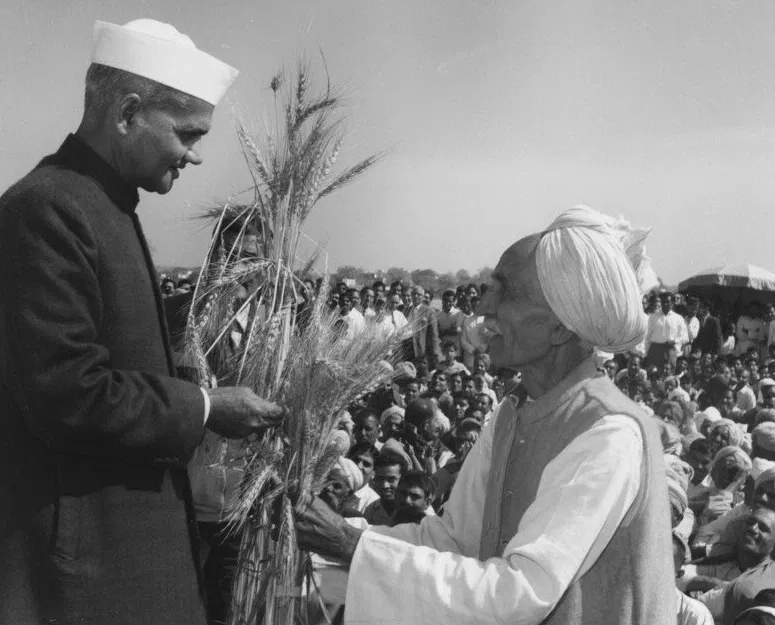

Shastri’s Defiance and the Seeds of Change

In 1965, Pakistan attacked India. Shastri now faced an impossible choice: deal with starvation or deal with the invasion. He chose to fight first. Indian forces destroyed 170 Pakistani tanks, including 97 American-made Patton tanks — machines considered unbeatable at the time. India shattered that reputation.

America was furious. President Lyndon Johnson threatened to cut off wheat shipments if India didn’t stop the war. Shastri’s response was blunt: America could keep its wheat, but India would keep fighting. That defiance came at a cost — the war disrupted development, and America continued dragging its feet on food deliveries.

But Shastri refused to grovel. In October 1965, on the day of Vijay Dashami at Delhi’s Ramlila Maidan, he gave India a rallying cry: “Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan” — hail the soldier, hail the farmer. He asked citizens to fast one day a week and eat more vegetables, but never to let the country bow before anyone.

Behind the slogans, Shastri was making hard strategic decisions. He increased the agriculture budget significantly. His Food and Agriculture Minister, C. Subramaniam, proposed a two-point formula to the cabinet: give farmers price incentives, and push for scientific farming. The proposal faced fierce political opposition, but Subramaniam held his ground — and won Shastri’s trust.

This is where the father of the Green Revolution in India enters the story. Subramaniam partnered with agronomist MS Swaminathan to launch a new agricultural program that would fundamentally change how India grew food.

MS Swaminathan: The Man Who Chose Farms Over Medicine

MS Swaminathan never planned to become the father of the Green Revolution in India. His father wanted him to be a doctor. But the Bengal famine of 1943 left such a deep mark on him that he abandoned a medical seat to study agriculture at Coimbatore Agricultural College. After graduating, he earned a postgraduate degree from the Indian Agricultural Research Institute in New Delhi and threw himself into farming research.

While Swaminathan was working on India’s agricultural problems, an experiment thousands of miles away was about to change everything. American agricultural scientist Norman Borlaug had moved to Mexico after completing his PhD in plant pathology and genetics at the University of Minnesota. There, he developed hybrid wheat seeds — varieties like Pitic 62 and Penjamo 62 — that resisted diseases and yielded several times more grain than traditional seeds.

In 1963, Borlaug planted these hybrid seeds across Mexico. The results were staggering: wheat production jumped sixfold compared to previous harvests. Swaminathan had been tracking Borlaug’s work closely, and this breakthrough convinced him to bring Borlaug to India.

In March 1963, Norman Borlaug arrived in India and toured several northern states, testing the new wheat varieties against Indian soil and climate. His estimate: the new seeds could produce 4 to 5 tons per hectare — double or more than India’s traditional varieties, which managed only about 2 tons per hectare.

What most people get wrong about the Green Revolution is treating it as a single scientific breakthrough. It wasn’t. It was an entire system — high-yielding variety seeds, adequate irrigation, fertilizers, and pesticides working together. The seeds were the catalyst, but without the supporting infrastructure, they would have produced modest gains at best.

When the Green Revolution Started in India: From Experiment to Transformation

Minister Subramaniam demonstrated his conviction in the most direct way possible — he grew the new wheat in front of his own house in Delhi to prove it worked in Indian conditions. With Shastri’s full backing, India imported over 18,000 tons of Mexican wheat seeds, including the Sonora 63, Sonora 64, Mayo 64, and Lerma Rojo 64 varieties.

The government distributed these seeds free of cost, primarily to farmers in Haryana, Punjab, and western Uttar Pradesh — regions that had better irrigation resources than the rest of the country. Subsidies on fertilizers and pesticides followed, giving farmers a financial reason to take the risk.

Then, on 11 January 1966, Shastri died in Tashkent. The country feared this agricultural revolution would die with him. It didn’t. Indira Gandhi became Prime Minister and continued supporting the program.

But her relationship with America took a sharp turn. During a 1966 visit to Washington, President Johnson was initially impressed — he even wanted to dance with her at a White House reception, which she declined. When the Vietnam War escalated, and Johnson wanted India’s support, Gandhi publicly opposed American involvement instead. Johnson retaliated by delaying PL 480 wheat shipments. Ships loaded with grain would sit in port, ready but undelivered.

Gandhi understood what Johnson was doing. She couldn’t fight back directly — not yet. So she waited for India’s harvests to improve.

The government introduced a Minimum Support Price (MSP) for wheat, guaranteeing farmers that even if their crops failed, the government would cover their losses. This built trust and encouraged widespread adoption of the new seeds.

The results were stunning. Within just four years, wheat production in India jumped from 12 million tons to 17 million tons. Within two more years, it doubled again. The government created a buffer stock of 10 million tons in 1970 to protect against bad monsoons. By 1970-71, total agricultural production had climbed to 108.4 million tons.

The Fourth Five-Year Plan, on Gandhi’s recommendation, refocused spending on agriculture. The Green Revolution expanded beyond wheat: rice cultivation experiments in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh proved equally successful. Those states remain among India’s top food producers to this day.

1971: India Breaks Free From American Leverage

By 1971, a new crisis tested India’s food security. Millions of refugees from East Pakistan flooded into India, fleeing atrocities by West Pakistan. India had barely recovered from decades of food shortages — absorbing millions more mouths seemed impossible.

Gandhi traveled to Washington to discuss the East Pakistan crisis with President Richard Nixon. He dismissed her concerns. When India went to war with Pakistan over East Pakistan later that year, America openly sided against India. Nixon threatened India, then sent the US Seventh Fleet toward the Indian Ocean.

None of it worked. India defeated Pakistan decisively and helped create Bangladesh as an independent nation. When Nixon tried the old playbook — threatening to withhold PL 480 grain — India had a different answer this time.

By 1971, India’s food production had grown enough to feed its entire population. A bumper harvest that year strengthened the country’s resolve. On 29 December 1971, India announced its exit from the PL 480 scheme — ahead of schedule. The message to America was unmistakable.

This is the moment that separates India’s Green Revolution from a mere agricultural program. It wasn’t just about growing more wheat. It was about dismantling a dependency that had been used as a diplomatic weapon for over a decade. Food self-sufficiency didn’t just fill stomachs — it gave India foreign policy freedom.

By 1978-79, India’s food production had reached 131 million tons, making it one of the world’s largest food producers. A country that once couldn’t feed itself was now exporting food to other nations. How food security was ensured in India is, at its core, this story — not just of seeds and fertilizers, but of political will meeting scientific innovation at exactly the right moment.

The Other Side: Negative Effects of the Green Revolution in India

Five decades later, the costs of the Green Revolution have become impossible to ignore. The drive for maximum production created a cycle of escalating chemical use — India is now the world’s second-largest consumer of fertilizers and pesticides after China. Over time, excessive fertilizer use stripped the soil of its natural fertility, making farmland less productive and the food it produces more contaminated.

The environmental damage extends further. Because wheat, rice, and maize became the most profitable crops under the new system, farmers in Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh abandoned pulses and oilseeds almost entirely. Their agriculture became a monoculture dependent on just two crops — wheat and paddy. Rice cultivation demands enormous amounts of water, and decades of intensive paddy farming have driven groundwater levels dangerously low in these regions, creating a water crisis that persists today.

The benefits also weren’t evenly distributed. Small farmers, who couldn’t afford the seeds, fertilizers, and irrigation infrastructure needed for high-yield farming, saw far less benefit than larger landholders. Even Swaminathan himself later acknowledged these negative effects of the Green Revolution in India. The government has since been forced to promote organic farming as a corrective measure.

Here’s the pattern worth recognizing: short-term solutions to urgent crises often create long-term structural problems. The Green Revolution solved India’s immediate food emergency — and that achievement is undeniable. But the single-minded focus on maximizing production, without accounting for ecological and social sustainability, planted seeds of a different kind of crisis.

Why This Story Still Matters

The journey from the Bengal famine to the India wheat export ban of 2022 spans eight decades and carries a lesson that goes beyond agriculture. When India banned wheat exports, it wasn’t an act of isolation — it was an exercise of power that would have been unimaginable when Shastri was asking citizens to skip meals once a week.

The father of the Green Revolution in India, MS Swaminathan, didn’t just introduce better seeds. He helped build a system — backed by political leaders like Shastri, Subramaniam, and Indira Gandhi — that broke a cycle of dependency stretching back to colonial rule. The fact that India now debates how to manage its food surplus, rather than where its next meal will come from, is the clearest measure of what that generation achieved.

The Green Revolution’s flaws are real. Its environmental costs demand urgent attention. But to dismiss it because of those costs is to forget what India looked like without it — a country where a third of the population went to bed hungry, where American newspapers drew Indians as beggars with bowls, and where a wheat shipment could be delayed as punishment for foreign policy disagreements. That is the India that the Green Revolution replaced.