The Galwan Valley clash of June 15, 2020, became the deadliest confrontation on the India-China border in over four decades. On that freezing night in eastern Ladakh, Indian and Chinese soldiers fought hand-to-hand at 14,000 feet. Historical records confirm that this battle significantly altered the strategic landscape between the two nuclear-armed nations.

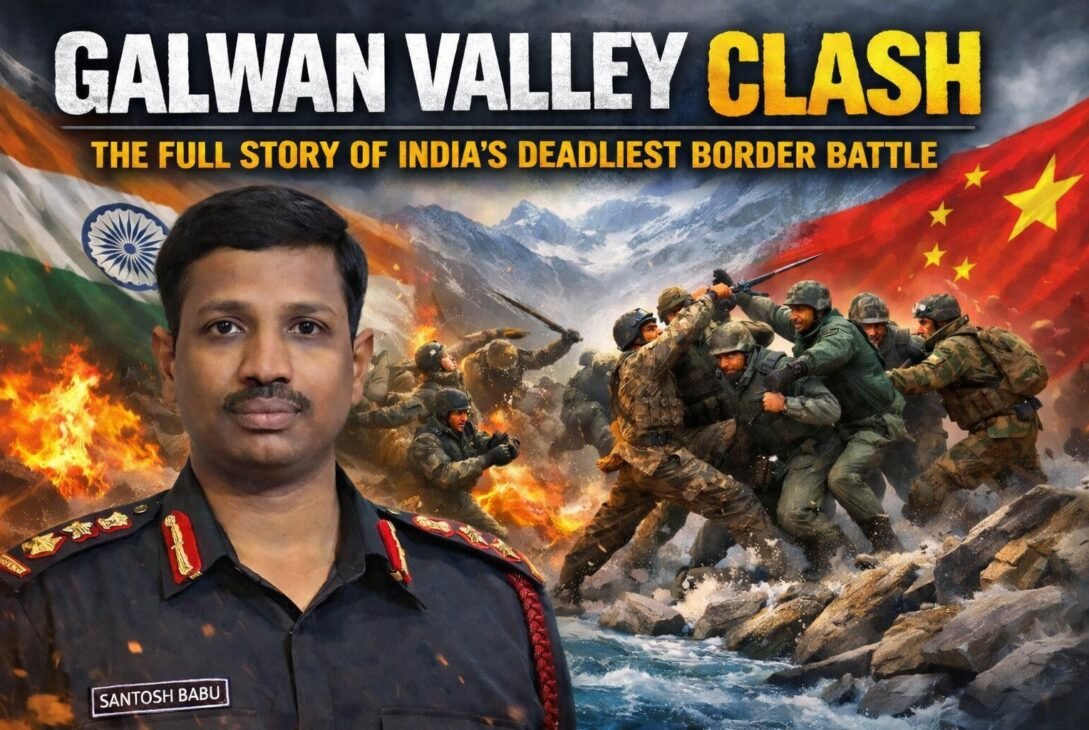

Colonel B. Santosh Babu, commanding officer of the 16th Bihar Regiment, led his soldiers against overwhelming odds. Twenty Indian soldiers were martyred. In return, Indian troops killed at least 43 Chinese soldiers. The Galwan Valley clash exposed China’s deception and India’s battlefield courage in equal measure.

This article covers the complete story behind the clash. It examines the roots of the India-China border dispute, the events leading to the confrontation, and its lasting consequences. Every detail here is based on documented accounts of the incident.

The India China Border Dispute: How It All Began

The India China border dispute has roots stretching back to the British colonial era. In the 20th century, the northern border of British India connected directly to Tibet. Tibet’s political situation remained unclear during this period. On the ground, Tibet ran its own government. In international documents, it was considered under the suzerainty of China’s Qing Dynasty.

This ambiguity meant Tibet was neither completely free nor fully a part of China. The British attempted to formalize the boundary of the Ladakh region within this confusion. These efforts created competing boundary lines that would haunt India-China relations for decades.

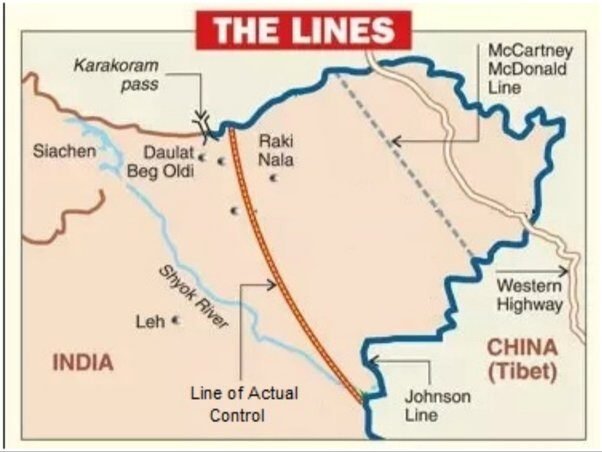

The Johnson Line and the McCartney-McDonald Line

In 1865, British surveyor W. H. Johnson proposed the Johnson Line. According to this line, the entire Aksai Chin was part of India. British India used this line in its maps. Tibet also accepted this boundary. From the perspective of both British India and Tibet, the Johnson Line was the accepted border.

China, however, did not accept this boundary. Britain did not want to upset China because of the rivalry called The Great Game between Russia and Britain. In 1899, the British sent China a proposal about the McCartney-McDonald Line. This proposal offered China a large share of Aksai Chin. But China did not accept this proposal either.

The situation was clear. British India and Tibet believed in the Johnson Line. Aksai Chin was part of India under this arrangement. China rejected both the Johnson Line and the McCartney-McDonald Line. This fundamental disagreement created the foundation of the dispute.

The McMahon Line and Tibet’s Fate

After the Qing Dynasty collapsed in 1912, Tibet became completely free from Chinese influence. The Shimla Convention took place between British India and Tibet in 1914. This convention drew a border line on the eastern side called the McMahon Line. Both British India and Tibet fully accepted this border.

China did not accept this agreement either. China kept showing disagreement but could not do anything significant about it. The story changed dramatically when Mao Zedong formed the People’s Republic of China in 1949. China invaded Tibet in 1950 and included it within its territory.

As soon as Tibet ended as an independent entity, India and China became direct neighbors. This was the moment the border issue became serious. China declared that the border between British India and Tibet was illegal. According to China, Tibet was never an independent state. China rejected everything from the Johnson Line to the McMahon Line.

From the 1962 War to the Line of Actual Control

After taking over Tibet, China started claiming India’s territory. China began telling the world that Aksai Chin was its share. Historically, this area was an integral part of Ladakh and had always appeared in India’s maps. Government historical records show that China’s intentions became clearer with each passing year.

In 1957, China secretly built a strategic highway called G219 in the middle of Aksai Chin. This highway connects Xinjiang with Tibet. India discovered this construction only later. Tension increased significantly after this revelation. But India was running a friendship policy of peaceful coexistence at the time. China took advantage of this diplomatic approach.

The 1962 Sino-Indian War

In 1961, China began aggressive patrolling and pushed back Indian troops near many posts. This tension turned into a full-fledged war in 1962. India was trying to solve the dispute diplomatically. China suddenly attacked in multiple sectors. China won this war and took over about 38,000 square kilometers of Aksai Chin.

Five years later, in 1967, China started invading the eastern side at Nathu La and Cho La. This time, the Indian soldiers responded decisively. Indian soldiers pushed the Chinese soldiers 3 km behind. They killed more than 350 Chinese soldiers and handed China a humiliating defeat.

What Is the Line of Actual Control?

Despite these conflicts, no formal border settlement emerged between the two countries. The Line of Actual Control, or LAC, became the de facto border. But it has never been clearly defined. There is no fixed line that both sides agree upon. There are neither physical pillars on the LAC nor a mutually agreed map.

India tried multiple times to sit with China and draw a clear border. China always avoided this process. The unclear border gives China a tactical advantage. Patrolling routes separated over time. Both sides started considering different places as their own territory. This confusion caused repeated clashes on the LAC border.

To prevent these clashes from escalating, India and China signed the Border Peace and Tranquility Agreement in 1993. Both countries agreed to maintain a status quo on the LAC. In 1996, another agreement called Confidence Building Measures was signed. The most important condition was that armies of both countries would not use guns, cannons, or explosive weapons near the LAC.

The Road to the Galwan Valley Clash: Events of 2019-2020

Scholarly research indicates that the Darbuk-Shyok-DBO road became a critical trigger for the conflict. India had understood that countering China effectively required strong infrastructure near the LAC. This 255-kilometer road connects Leh to the strategically vital Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO) area.

The work on this road started in 2000 but faced continuous delays. The Indian government accelerated construction in 2019 and set a target to complete it within a year. DBO is located between Shyok and Karakoram Pass. This area sits at more than 16,000 feet and serves as an important advanced landing ground for the Indian Air Force.

China’s Opposition to India’s Infrastructure

A branch of the Darbuk-Shyok-DBO road goes towards the Galwan Valley. This is where China’s real opposition began. China understood that India was building permanent road access. A completed road would make India’s presence stronger in the region. This went against China’s strategy.

China sent artillery guns to the LAC near its military bases. Infantry Combat Vehicles and Heavy Military Equipment were suddenly increased. India called this road its sovereign right. China called it a threat to its territorial integrity. These disagreements were heading towards a major clash.

Tensions Escalate on Multiple Fronts

By early 2020, India and China increased patrolling on the LAC. Clashes broke out at Pangong Tso Lake and Hot Springs patrol routes. Chinese troops constantly tried to enter the frontier areas. These areas had long been part of the Indian patrol route. Due to the no-firearms agreement, there was no firing. But pushing, elbowing, and physical obstruction became common.

In May 2020, Chinese troop mobilization suddenly increased. On May 21, Chinese troops entered Indian territory in the Galwan Valley. They set up 70-80 tents against the Darbuk-Shyok-DBO road. On May 24, Chinese soldiers entered Hot Springs and Patrol Point 14, going 3 km inside the LAC. India responded by stationing its troops about half a kilometer from the Chinese positions.

The situation deteriorated so badly that senior military commanders held a seven-hour meeting in Ladakh on June 6, 2020. Both countries agreed to withdraw their armies 2 km from Patrol Point 14. China agreed to withdraw its 1,000 soldiers stationed at the LAC. But China’s compliance lasted only a few days. New tents appeared at the same location. This was a direct violation of military protocol.

The Galwan Valley Attack: What Happened on the Night of June 15, 2020

Contemporary accounts verify that on the evening of June 15, Colonel B. Santosh Babu reached Patrol Point 14 with about 30 soldiers. They needed to verify whether China had followed the disengagement terms from the June 6 meeting. Chinese troops were supposed to remove all temporary structures and observation posts.

But as the Indian soldiers reached the turn of the Galwan River, they found that the Chinese had re-established many structures. Despite this provocation, Colonel Santosh Babu remained calm. He told the Chinese soldiers that the post violated the agreement and must be removed immediately.

The First Confrontation

The Chinese soldiers responded with hostility. One of them ran towards Colonel Santosh Babu and pushed him hard. Colonel Santosh Babu stood firm. His soldiers could not tolerate this insult to their commanding officer. The Indian soldiers fell on the Chinese, and the confrontation turned into a fierce fight within seconds.

The Indian soldiers completely destroyed the Chinese observation post and set it on fire. The Chinese soldiers retreated due to their reduced numbers. Colonel Santosh Babu sensed that the Chinese would return to avenge this humiliation. His instinct proved correct.

The Ambush: 300-400 Chinese Troops Return

Taking advantage of the darkness, Chinese soldiers returned in a force of 300 to 400. They came fully prepared with iron rods, big stones, spiked clubs, and barbed wire wrapped rods. Many wore bulletproof jackets. It was clear that China had planned this clash from the beginning.

They started throwing large pointed stones at the Indian soldiers. A fierce hand-to-hand combat began on the rocky mountains at 14,000 feet. About 30 Indian soldiers without weapons faced 300 to 400 Chinese troops armed with iron rods and barbed wire clubs. Reports suggest the Chinese also had electromagnetic stun-type devices.

Despite being outnumbered and outequipped, Indian soldiers refused to retreat. Nails got stuck in their bodies. Stones caused severe bleeding. But not a single soldier moved back. Even while injured, they grabbed the Chinese soldiers’ weapons and turned them against their owners.

Colonel Santosh Babu’s Last Stand

Colonel Santosh Babu led from the front with extraordinary courage. He was at the forefront of the fight, engaging the Chinese directly. At about 9 o’clock at night, Chinese soldiers threw a large stone that hit him hard on the head. He was badly injured and fell into the rapid flow of the Galwan River. He died fighting for his country.

Two more Indian soldiers were martyred shortly after. The remaining soldiers’ anger was beyond control. They counterattacked with everything they had. The Indian soldiers immediately called for reinforcements from a nearby military post only 3 km away. About 200 Indian soldiers arrived as reinforcements. The fight became even more fierce.

To counter the Chinese soldiers’ nail-studded sticks and iron rods, Indian soldiers fixed bayonets to their rifles. They launched a relentless assault. The Chinese soldiers’ own violence backfired on them. They realized they were facing soldiers who would risk everything to defend their homeland.

Six Hours of Battle

This fierce battle dragged on for six hours in complete darkness and minus temperatures. The narrow and steep terrain of the Galwan Valley made the struggle even more deadly. Many soldiers fell from the 14,000-foot heights while fighting. Some soldiers accidentally crossed the LAC. Both sides captured each other’s soldiers.

A total of 20 Indian soldiers were martyred. In return, Indian troops killed at least 43 Chinese soldiers and seriously injured many more. Before the morning of June 16, military officials from both countries agreed to stop the battle. They agreed to recover bodies and evacuate injured soldiers. A major general-level talk followed, and captured soldiers on both sides were returned.

Colonel Santosh Babu: The Hero of Galwan Valley

Colonel B. Santosh Babu was born on February 13, 1983, in the Suryapet district of Telangana. He started his studies at Shri Saraswati Shishu Mandir School and continued at Korukonda’s Sainik School. After leaving Sainik School, he was passionate about joining the Indian Army.

He passed the National Defence Academy (NDA) exam and joined the NDA in December 2000. He then trained at the Indian Military Academy. On December 10, 2004, he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the 16th Bihar Regiment. This regiment is known for its bravery and discipline.

His first posting was in Jammu. He served in important roles, including platoon commander, anti-tank platoon commander, and rifle company commander. His experience in counter-insurgency and counter-infiltration operations made him a calm and sharp-minded officer. Despite his soft-spoken nature, he always led from the front.

Colonel Santosh Babu was awarded the Mahavir Chakra posthumously. This is India’s second-highest wartime gallantry decoration. On January 26, 2021, the Indian government honored all soldiers martyred in Galwan Valley. Several others received the Vir Chakra, Kirti Chakra, and Shaurya Chakra. These honors are typically given during wartime. Before this, such honors were last given during the Kargil War of 1999.

Aftermath: India’s Military and Economic Response

India officially accepted that 20 soldiers were martyred. China initially tried to hide its casualties completely. The Chinese government claimed no soldiers were killed. Multiple sources soon exposed this lie. The Australian newspaper The Klaxon reported 38 Chinese soldiers killed. The Russian news agency TASS claimed 43 Chinese soldiers were killed.

After the Russian report, China accepted losses for the first time. But it claimed only four soldiers died. The documented evidence demonstrates that China also falsely claimed the clash happened in the Chinese part of the LAC. India rejected this and confirmed the clash occurred in the Indian section.

India’s Military Escalation

Two days after the clash, the Indian Air Force Chief arrived in Leh for a ground assessment. He reviewed preparedness at Srinagar Air Base the next day. The Indian Air Force deployed Sukhoi-30MKI, Mirage 2000, and Jaguar aircraft on a forward basis. Apache and Chinook helicopters were deployed at critical sectors of the China border.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi clearly stated that the soldiers’ sacrifice would not go in vain. China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi had to call Indian Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar. But India did not soften its stance. S. Jaishankar clearly said that whatever happened in Galwan was China’s responsibility. Defence Minister Rajnath Singh authorized Indian Field Commanders to use weapons according to the situation. This was the first change in the rules of engagement of this kind.

Economic Countermeasures

India also struck China on the economic front. India banned 220 Chinese apps. The government said these apps stored data on servers outside India, threatening national security. The banned list included apps from Alibaba Group, Tencent, Baidu, TikTok, WeChat, PUBG, and ByteDance.

India suspended tourist visas, business visas, and student visas for Chinese citizens. On July 3, Prime Minister Modi himself reached Ladakh, met with soldiers, and gave the message that India would not back down.

Disengagement, Ongoing Tensions, and the India-China Cold Peace

Russia intervened as a mediator between the two countries. On September 5, 2020, India and China’s Defence Ministers and Foreign Ministers met in Moscow. But peace talks turned into accusations. Two days later, firing took place between the two armies at the LAC. This was the first time in 45 years that bullets were fired at the India-China border.

On September 22, 2020, both countries issued their first joint statement after the Galwan Valley clash. They agreed not to send additional troops to the border. About 10 months later, on February 10, 2021, the two countries signed a peace agreement for the Pangong Tso area.

The 2022 Tawang Clash and 2024 Agreements

In December 2022, China dispatched 300 soldiers to remove an Indian post in the Yangtze area of Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh. Indian soldiers answered decisively. Chinese soldiers had to leave their bags and retreat. This proved again that China could never be a reliable neighbor.

In October 2024, India and China agreed to restore the pre-2020 situation on the LAC. Disengagement and new patrol arrangements were agreed upon in Depsang and Demchok. These were two critical points where the Chinese army had blocked since 2020.

Buffer Zone Concerns and Strategic Analysis

However, the ground situation remained complicated. Buffer zones created after 2020 were not revisited. These zones effectively turned several areas where India previously patrolled into no-patrol zones. Former Ambassador to China Ashok Kantha stated that India had lowered the benchmark for disengagement.

Strategic thinkers, including Dr. Brahma Chellaney, argued that India compromised on China’s terms. Under the guise of disengagement, China presented India with a model that pushed India back within its own territory. Indian troops withdrew, but Chinese forward deployment structures and logistics capabilities remained intact. China’s leverage on the LAC did not decrease but increased in several sectors.

The 2025 Arunachal Pradesh Incident

In November 2025, China showed again that normalization was impossible. An Indian citizen of Arunachal Pradesh, Prema Wong Thongdok, was detained by Chinese officials at Shanghai Pudong Airport for about 18 hours. She was transiting through Shanghai on her way from London to Japan. Chinese immigration declared her Indian passport invalid because it listed Arunachal Pradesh as her birthplace.

China calls Arunachal Pradesh “South Tibet.” India has repeatedly clarified that Arunachal Pradesh is an integral part of India with no Chinese claim. India lodged strong diplomatic protests and called this act unacceptable. This incident demonstrated that China does not miss any opportunity to advance its territorial false narrative.

Conclusion: Why the Galwan Valley Clash Remains a Defining Moment

The Galwan Valley clash stands as a defining moment in modern India-China relations. It shattered the illusion that economic ties could prevent military confrontation. It proved that China can break agreements and attack without provocation. The battle also demonstrated that Indian soldiers will fight to the last breath even without weapons.

India-China relations today can best be described as a cold peace. Neither side wants open war. Neither side can truly be friends. The India China border dispute remains unresolved. The Line of Actual Control continues without clear definition. In this uncertain reality, the Galwan Valley clash serves as a permanent reminder that India must remain constantly alert.

Colonel Santosh Babu and the 19 other martyrs gave their lives defending India’s sovereignty at Galwan. Their sacrifice ensured that the world understood one truth: Indian soldiers do not retreat, no matter the odds.