Two thousand three hundred years before the first British officer stamped an income tax notice in India, a Mauryan economist had already written the rulebook. Kautilya’s Arthasastra didn’t just mention taxes — it laid out rates, exemptions, collection procedures, and even penalties for evasion. The history of income tax in India isn’t a story that begins in the colonial era. It begins in the courts of ancient kings who understood something many modern governments still struggle with: that taxation is a contract between the state and its people.

And yet, most accounts of Indian tax history begin in 1922 — when the British formalised the Income Tax Act — as if nothing came before. That framing misses the fact that Mauryan-era tax rates, exemption categories, and collection hierarchies map surprisingly well onto modern systems. The gap between Kautilya and the CBDT is shorter than it looks.

Taxation in Ancient India: Manu, Kautilya, and the Arthasastra

Most people assume India’s tax history starts with the British. That assumption is off by a couple of millennia.

Both the Manu Smriti and Kautilya’s Arthasastra contain detailed references to a variety of tax measures. Manu, the ancient sage and lawgiver, stated that the king could levy taxes according to the Sastras—but with a critical condition. He cautioned against excessive taxation and argued that both extremes should be avoided: complete absence of taxes or exorbitant taxation. The king, Manu advised, should arrange collection in such a manner that subjects did not feel the pinch of paying.

Here’s where it gets specific. Manu laid down that traders and artisans should pay 1/5th of their profits in silver and gold, while agriculturists were to pay 1/6th, 1/8th, or 1/10th of their produce depending on their circumstances. Taxes were also levied on actors, dancers, singers, and even dancing girls. Payments were made in the form of gold coins, cattle, grains, raw materials, and personal services.

As K.B. Sarkar notes in Public Finance in Ancient India (1978 Edition), the tax structure in ancient India was broad-based, covering most people within its fold, and the admixture of direct taxes with indirect taxes secured elasticity in the system.

Kautilya’s Arthasastra: The First Tax Code

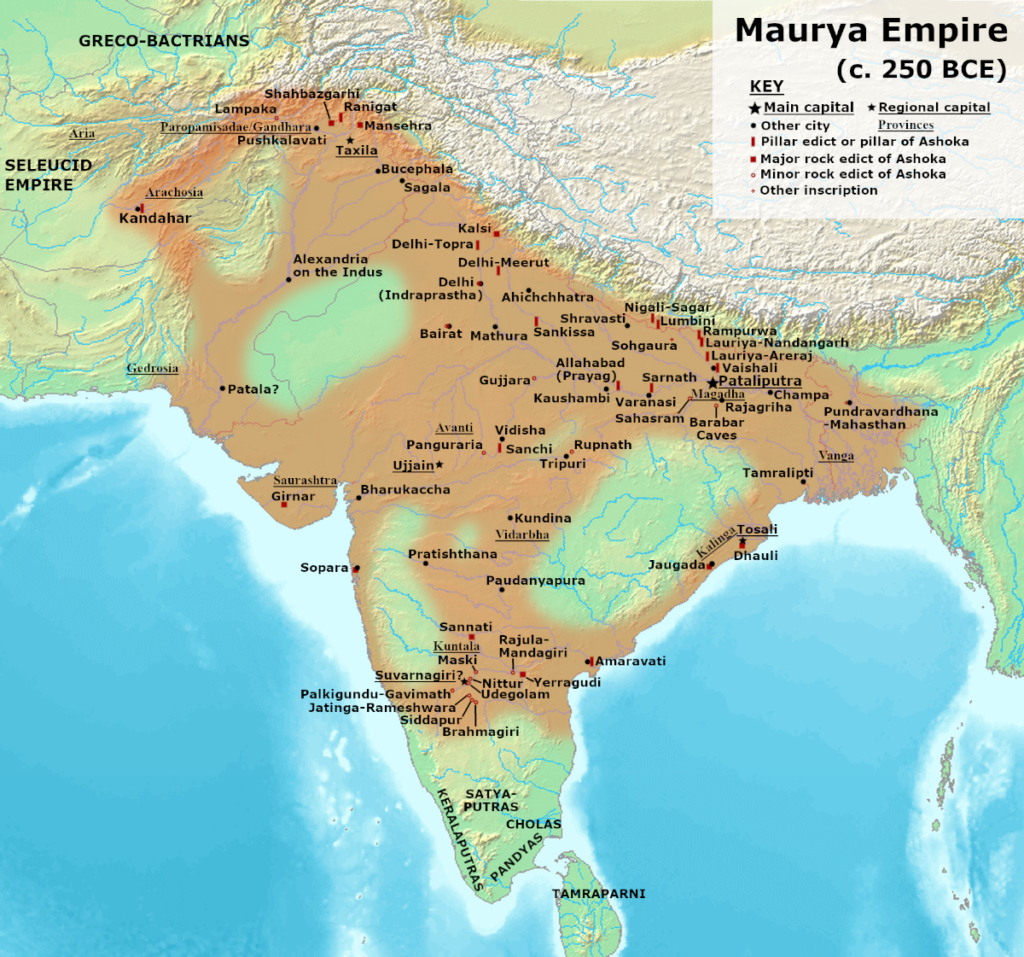

But it’s Kautilya’s Arthasastra — written around 300 B.C., when the Mauryan Empire was at its peak — that reads like an actual tax administration manual. A major portion of this treatise on statecraft is devoted to financial matters, and the depth is startling for a text that old.

The Mauryan system treated land revenue as a principal source of state income, with the standard rate fixed at 1/6th of agricultural produce. Beyond that, the state levied water rates, octroi duties, tolls, customs duties, and taxes on forest produce and mining. Salt tax was collected at the point of extraction. Import duties on foreign goods were roughly 20 percent of their value, collected through levies like the Vartanam on foreign commodities and the Dvarodaya paid by importers. Ferry fees of all kinds rounded out the collection.

Income tax collection was well-organised and constituted a major part of state revenue. Taxation was proportional to fluctuating income — not progressive, but responsive. An excess profits tax was collected. General sales tax covered transactions, including the purchase of buildings. Even gambling operations were centralised and taxed. A levy called yatravetana applied to pilgrims.

One way to read this system is as remarkably modern in intent. Kautilya’s emphasis on equity — the affluent paying higher taxes, exemptions for the sick, for minors, and for students — mirrors principles that wouldn’t formally enter European tax law for centuries.

Tax as a Social Contract, Not Extraction

You might wonder what separated Kautilya’s approach from simple state extraction. The answer is philosophy.

According to the Arthasastra, tax was not a compulsory contribution to be made by the subject to the state. The relationship was based on Dharma. The king was a trustee of the land — his duty was to protect it and make it productive. If the king failed in this duty, the subject had a right to stop paying taxes and even demand a refund. Revenue was spent on social services: laying roads, setting up educational institutions, and establishing new villages.

Kautilya stated it plainly: the power of government depended upon the strength of its treasury. But the treasury existed to serve the people. This wasn’t charity — it was an explicit bargain. And it was codified with a precision that makes the Arthasastra, as many scholars argue, the first authoritative text on public finance in India.

During emergencies like war, famine, or floods, the system became more stringent. Land revenue could be raised from 1/6th to 1/4th. Commerce was expected to make big donations to war efforts. Tax evaders were fined to the tune of 600 panas. Even the Arthasastra understood that fiscal policy needs a crisis gear.

The Income Tax Act 1922: Where Modern Administration Begins

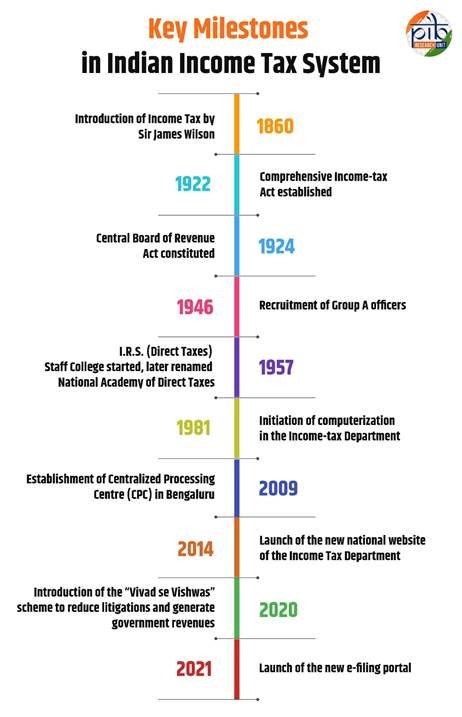

Fast-forward past the Mughal revenue systems and colonial experiments, and the organisational history of the Income-tax Department starts cleanly in 1922. The Income Tax Act 1922 gave, for the first time, a specific nomenclature to various income-tax authorities. It laid the foundation of a proper administrative system.

In 1924, the Central Board of Revenue Act constituted the Board as a statutory body with functional responsibilities. Commissioners of Income-tax were appointed separately for each province, with Assistant Commissioners and Income-tax Officers under their control. The scaffolding of a formal, hierarchical tax administration was taking shape.

The 1939 amendments introduced two structural changes that still echo today. Appellate functions were separated from administrative functions — creating a class of officers known as Appellate Assistant Commissioners. And a central charge was created in Bombay. By 1941, the separation of executive and judicial functions had given rise to the Appellate Tribunal. A central charge was created in Calcutta in the same year.

World War II and the Birth of Investigation

World War II changed the equation. Unusual profits flowed to businessmen during wartime, and the government responded with the Excess Profits Tax (introduced for the period starting 1-9-1939) and the Business Profits Tax (enacted for 1-4-1946 to 31-3-1949). Both were eventually repealed, but they established a pattern: economic disruption brings new tax instruments.

In 1946, a few Group ‘A’ officers were directly recruited for the first time. In 1947, the Taxation on Income (Investigation) Commission was set up — later declared ultra vires by the Supreme Court in 1956, but not before it had established the necessity of deep investigation. The Directorate of Inspection (Investigation) followed in 1952, along with a new cadre of Inspectors of Income Tax. In 1953, the Group ‘A’ Service was formally constituted as the Indian Revenue Service.

What most people get wrong about this period is treating it as purely administrative bookkeeping. It wasn’t. The Indian government was building, from nearly nothing, an institutional infrastructure to track income across a newly independent nation of hundreds of millions. The 1951 Voluntary Disclosure Scheme — the first of several — reveals just how wide the gap was between tax liability and actual collection. The gap wasn’t just bureaucratic; it was informational.

The CBDT and the Expanding Tax Universe (1960s–1980s)

By 1963, the Income-tax Department had been burdened with administering the Wealth Tax Act (1957), the Gift Tax Act (1958), the Estate Duty Act (1953), and more. It had expanded to such an extent that a separate board was deemed necessary. The Central Board of Revenue Act, 1963, led to the creation of the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT). For the first time, in 1964, an officer from within the department became Chairman of the CBDT.

The Income-tax Act, 1961, had already come into existence w.e.f. 1-4-1962, replacing the 1922 Act. But the traces of the old act had been evolving so rapidly that, as official records note, except in the bare outlines, the 1922 Act could hardly be recognised in the 1961 version as it stood amended.

This era brought steep tax rates and, inevitably, black incomes. The Voluntary Disclosure Scheme returned in 1965 and again in 1975. A Settlement Commission was eventually created in 1976. The pattern kept repeating: raise rates, see evasion rise, offer amnesty, tighten investigation, repeat.

Administrative Machinery Gets Heavier

The 1970s and early 1980s saw a cascade of institutional changes. Recovery of tax arrears, previously handled by state authorities, was transferred to departmental Tax Recovery Officers in 1970. New cadres were created — IAC (Assessment) in 1977, CIT (Appeals) in 1978. Five posts of Chief Commissioner (Administration) were created in 1981. The Permanent Account Number (PAN) system was introduced in 1972, a precursor to the data infrastructure that would eventually underpin everything.

Each of these changes was a response to a specific failure or bottleneck. Consider the PAN system: without a unique identifier linking taxpayers to their transactions, the department was effectively flying blind. What seems like a routine administrative step was actually a foundational shift toward data-driven taxation — a thread that runs all the way to Aadhaar-PAN linkage decades later.

Computerisation and the Digital Leap (1981–2010)

Computerisation in the Income-tax Department started with the setting up of the Directorate of Income Tax (Systems) in 1981. The first three computer centres came up in 1984–85 in metropolitan cities using SN-73 systems, initially just for processing challans. By 1989, this had expanded to 33 major cities.

The real acceleration came in 1993, when a Working Group recommended comprehensive computerisation. Regional Computer Centres were established in Delhi, Mumbai, and Chennai in 1994–95. A National Computer Centre was set up in Delhi in 1996–97. PCs reached officers at various levels between 1997 and 1999. By the time Phase II rolled out, offices in 57 cities were networked and linked.

The income tax history of this period is really a story about information. The department went from paper files and physical ledgers to networked databases in roughly 15 years. The National Website launched in 2002. E-filing of returns launched in 2006. The Centralized Processing Centre was set up in Bengaluru in 2009, processing returns without any interface with taxpayers in a jurisdiction-free manner. By 2007–08, the Income Tax Department had become the government’s biggest revenue mobiliser, with its share increasing from 34.76% in 1997–98 to 52.75% in 2007–08.

The Integrated Taxpayer Data Management System (ITDMS), which enabled a 360-degree taxpayer profile, won the Prime Minister’s Award for Excellence in Governance and Administration in 2010.

Why Digitisation Mattered More Than Rate Changes

Here’s what’s often missed in the tax history narrative: the rate cuts of the 1990s and 2000s get the headlines, but it was computerisation that actually moved the needle on compliance. When you can match PAN data to bank transactions, property records, and investment accounts, the cost of evasion rises sharply. The shift from presumptive taxation to data-backed assessment — from guessing a taxpayer’s income to tracking it — was more consequential than any single rate change.

Tax Reforms and Modern Restructuring (2000–2022)

The income tax department restructuring approved by the Cabinet on 31-8-2000 targeted specific objectives: increased effectiveness and productivity, improved taxpayer services, workforce reduction from 61,031 to 58,315, and standardisation of work norms. The strategy was threefold — redesign business processes, rationalise supervisory spans, and retrain existing staff.

The Kelkar Committee Report in 2002 pushed further, recommending the outsourcing of non-core functions and the reduction in exemptions, deductions, reliefs, and rebates. The Annual Information Return (AIR) was introduced in 2004 to widen the tax base. Fringe Benefit Tax, Securities Transaction Tax, and Banking Cash Transaction Tax arrived between 2004 and 2005 as new instruments for capturing previously untaxed economic activity.

The Faceless Era

The most radical shift came in 2019 and 2020. The Faceless Assessment Scheme 2020 and Faceless Appeal Scheme 2020 removed the human interface entirely from assessment proceedings. No physical meetings. No local jurisdiction. Cases are assigned randomly to officers anywhere in the country.

Consider what this meant in practice. For decades, the relationship between a taxpayer and their assessing officer had been defined by geography and, sometimes, by familiarity. Faceless assessment broke that link deliberately. Whether this has fully achieved its aim of reducing corruption and bias is still being measured, but the structural intent is unmistakable.

Alongside this, PAN and Aadhaar became interchangeable in 2019. Document Identification Numbers (DIN) were introduced for all departmental communications. The new e-filing portal launched in 2021. Virtual Digital Assets came under the tax net in 2022. The Updated Return facility allowed filing even after the due date for belated or revised returns had expired.

From the Arthasastra to Algorithms: What the Arc Tells Us

What connects a Mauryan-era treatise on statecraft to a Bengaluru server farm processing millions of returns isn’t just the concept of tax. It’s the recurring tension between collection and fairness, between state power and citizen trust.

Kautilya framed the king as a trustee who owed protection in exchange for revenue. The 1922 Act created formal roles and accountability. The CBDT centralised authority. Computerisation created visibility. Faceless assessment removed personal discretion. Each step was an attempt to address the same underlying problem: how do you collect revenue at scale without losing legitimacy?

The history of income tax in India is still being written. But the pattern is clear enough. Every generation of policymakers has reached for the same two levers — better information and fairer rules — and the ones who pulled both at once tended to get the best results.