Introduction: The Anglicist–Orientalist Divide

The early 19th century saw a sharp divide between Orientalists and Anglicists over state-funded education. Orientalists claimed that Arabic and Sanskrit learning preserved “native literature,” while Anglicists argued for modern Western sciences and English education.

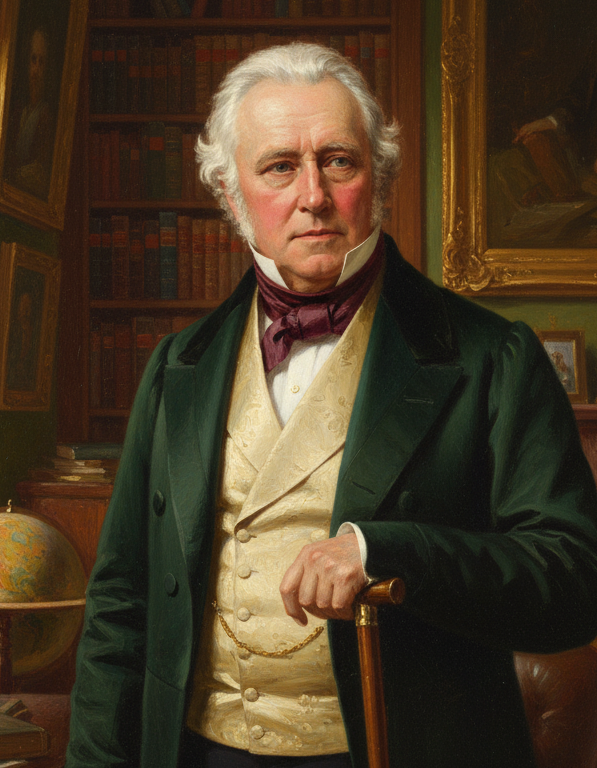

Thomas Babington Macaulay’s Minute on Education (1835) became the decisive Anglicist manifesto that redefined learning in India.

Utility Over Tradition: “What Is Best Worth Knowing?”

Macaulay insisted that public funds must teach what is “best worth knowing.” He asserted that Oriental learning lacked valuable scientific or historical knowledge.

His most famous claim set the tone: “A single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.”

He rejected the argument that Parliament intended exclusive support for Sanskrit or Arabic literature. To him, the duty was clear: promote knowledge that improved the intellect and served practical needs.

Why English? Macaulay’s Case for “Useful Knowledge”

Macaulay argued that English gave Indians access to the world’s richest intellectual tradition. English, he wrote, contained “the most profound speculations on metaphysics, morals, government, jurisprudence, trade,” and offered every branch of modern science.

Teaching Sanskrit or Arabic, he insisted, meant teaching “astronomy which would move laughter in girls at an English boarding-school” and “medical doctrines which would disgrace an English farrier.”

His point was blunt: Western sciences had surpassed all Eastern systems. “Wherever they differ, they differ for the worse.”

The Market Test: What Students Actually Wanted

One of Macaulay’s strongest empirical arguments was economic demand. Arabic and Sanskrit students had to be paid stipends to attend classes, while English students were willing to pay fees.

He presented hard numbers: the Calcutta Madrasa paid above 500 rupees a month in stipends, while English education generated revenue—students paid 103 rupees in a single quarter.

He called this “the detective test”:

If knowledge is useful, people pay for it.

If knowledge is useless, the state must bribe learners.

He also noted that 23,000 printed Arabic and Sanskrit volumes were gathering dust in “lumber-rooms” because no one bought them. Meanwhile, the School Book Society sold “seven or eight thousand” English books annually at a profit.

Creating a “Class of Interpreters”: The Downward Filtration Strategy

Macaulay acknowledged that the government could not educate the masses directly. Instead, he proposed forming “a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.”

This class would refine the vernacular, translate scientific knowledge, and eventually disseminate modern ideas to the population.

This became known as the Downward Filtration Theory—teach the elite, who then teach the masses.

Dismantling Counter-Arguments

1. “Public Faith” Was Not Pledged

Orientalists claimed that the government was bound to support traditional learning. Macaulay dismissed this as “unmeaning.”

No government, he argued, can pledge itself to promote outdated sciences “though those sciences may be exploded.”

2. Law and Religion Do Not Require Oriental Languages

Some said Sanskrit and Arabic were essential for law and religion. Macaulay countered that legal codification would make the Shastras and Hedaya irrelevant.

Supporting a language because it contained “serious errors on the most important subjects,” he argued, violated even the principle of religious neutrality.

3. The “Smattering of English” Argument Was False

Orientalists claimed Indians could only learn a “smattering” of English. Macaulay mocked this as baseless.

He observed that many Indians already discussed complex issues in English “with fluency and precision,” often better than foreigners in Europe.

Immediate Recommendations

Macaulay called for a complete restructuring of educational funding.

He urged:

- Stop printing Arabic and Sanskrit books.

- Abolish the Calcutta Madrasa and Sanskrit College.

- Keep only Benares and Delhi colleges, but end all stipends.

- Use the freed funds to strengthen English-medium education, especially the Hindu College at Calcutta.

These proposals guided Governor-General William Bentinck’s decision to adopt English as the official medium for higher education in India.

The Lasting Legacy: English as India’s Intellectual Gateway

Macaulay’s Minute became the ideological foundation of modern education in India. It dramatically shifted state support away from classical Indian learning. English became the gateway to administration, law, science, and modern professions.

While controversial, his policy set India on a path toward global intellectual integration.

Conclusion

Macaulay’s Minute of 1835 was not just a policy document. It was a manifesto that reoriented India’s educational philosophy around modernity, science, and global knowledge.

His arguments—harsh, dismissive, and influential—reshaped Indian aspirations for generations.