The Indian Ocean has become the world’s most contested maritime theater. Two rival strategies—China’s aggressive String of Pearls, China’s encirclement, and India’s defensive Necklace of Diamonds response are reshaping global geopolitics. This silent naval chess match will determine who controls the arteries of world trade for the next century.

At stake is control over 80% of global maritime oil trade, critical shipping lanes connecting three continents, and the economic future of 2.6 billion people. China’s String of Pearls strategy seeks to dominate through port investments and naval bases from Pakistan to Djibouti. Meanwhile, India’s Necklace of Diamonds counters with strategic partnerships across the same waters. This comprehensive analysis reveals how these competing visions are transforming the India-China Indian Ocean rivalry into the defining geopolitical contest of our era.

Understanding these strategies isn’t just academic—it determines which nation will shape global trade, energy security, and military balance in the world’s most strategically vital ocean.

The String of Pearls China Strategy: Encircling India

The String of Pearls China represents Beijing’s systematic plan to establish a network of ports, naval bases, and infrastructure projects encircling India throughout the Indian Ocean Region. This strategy exploits economically vulnerable nations through massive investments, creating both commercial leverage and military staging points.

China has invested billions in countries like Djibouti, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Pakistan. These investments aren’t merely economic—they’re strategic pieces in a larger game. By building refineries, high-speed data cables, railway lines, and gas pipelines, China creates alternate trade corridors that bypass Indian territory entirely.

Railway Networks: Land Routes to Global Dominance

The String of Pearls China extends beyond maritime infrastructure. China has developed an ambitious railway network stretching from London to Beijing, creating overland trade routes independent of sea chokepoints. Another critical route connects China to Iran via Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, terminating in Tehran.

These corridors serve China’s vision of becoming a global economic superpower by establishing independent supply chains and trade routes. Simultaneously, they provide military and economic leverage over rivals like India and the United States. Every infrastructure project strengthens China’s ability to project power across Eurasia.

Why the Indian Ocean Matters: Alfred Thayer Mahan’s Prophecy

To understand the India-China Indian Ocean competition, we must first grasp why this ocean holds such strategic importance. Historian Alfred Thayer Mahan captured this perfectly: “Whoever conquers the Indian Ocean will dominate the whole of Asia.”

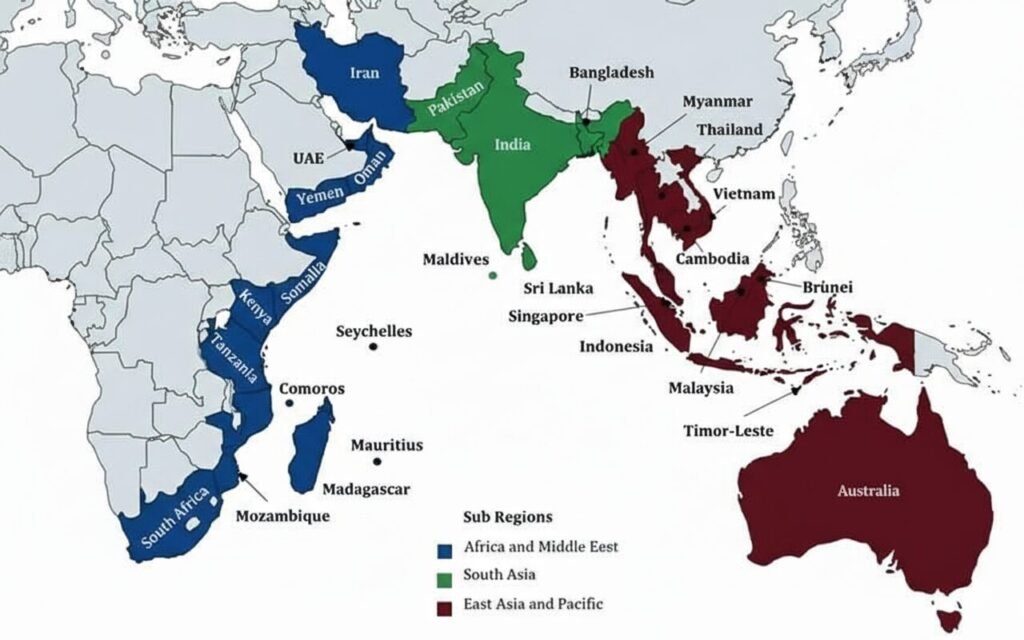

This nineteenth-century prediction has proven remarkably prescient. The Indian Ocean region encompasses 28 countries across three continents, covering 17.5% of global land area. More critically, it hosts over 35% of the world’s population—approximately 2.6 billion people. Twenty-one members belong to the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), including Australia, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Malaysia, Oman, Singapore, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Thailand, the UAE, and Yemen.

The Bridge Between Continents

The Indian Ocean serves as a vital bridge connecting North Atlantic economies to Asia-Pacific markets. It houses the world’s most important maritime trade routes, linking the Middle East, Africa, and East Asia with Europe and America. This geographic position makes it irreplaceable in global commerce.

Most remarkably, 80% of the world’s maritime oil trade flows through just three narrow chokepoints in the Indian Ocean. Control these passages, and you control global energy supplies. Lose control, and your economy becomes vulnerable to distant powers.

The Three Critical Chokepoints: Where Global Trade Hangs in Balance

The Strait of Malacca’s importance cannot be overstated—it’s one of three passages that determine global economic flow. Understanding these chokepoints reveals why the String of Pearls China targets them specifically.

The Strait of Hormuz connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman. This narrow passage handles the majority of Middle Eastern oil exports. Any disruption here sends global energy prices soaring.

The Strait of Malacca separates the Malay Peninsula from Sumatra, connecting the Indian Ocean to the Pacific. Over 25% of global trade passes through this 1.5-mile-wide channel. The Strait of Malacca’s importance extends beyond commerce—it’s the primary route for Chinese oil imports from the Middle East.

The Strait of Bab el-Mandeb links the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden, positioned between Yemen, Djibouti, and Eritrea. It controls access to the Suez Canal, making it critical for Europe-Asia trade.

Other Vital Maritime Passages

Beyond the big three, several other passages carry immense strategic weight. The Mozambique Channel between Madagascar and mainland Africa provides an alternate route around the Cape of Good Hope. The Sunda Strait and Lombok Strait offer secondary passages between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, though neither matches the Strait of Malacca’s capacity.

These chokepoints are so crucial that gaining control can halt global trade. Conversely, a lack of control exposes nations like India to significant vulnerability. China’s aggressive positioning near every major chokepoint reveals clear intentions to dominate maritime commerce.

How the String of Pearls China Strategy Controls Chokepoints

China has made calculated advances near all major passages. To dominate the Strait of Hormuz region, China secured a 40-year lease on Pakistan’s Gwadar Port. This deep-water facility sits at the entrance to the Persian Gulf, allowing China to monitor and potentially control oil shipments from the Middle East.

Additionally, China built rail infrastructure connecting Gwadar directly to western China, bypassing the Strait of Malacca entirely for Central Asian trade. This China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) represents a $62 billion investment, cementing Pakistan’s role in the String of Pearls China network.

Near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and Suez Canal, China established its first overseas naval base in Djibouti in 2017. This facility houses thousands of personnel and provides logistics support for naval operations across the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. China now has a permanent military presence controlling access to Europe-bound shipping.

Southeast Asian Expansion

For the Strait of Malacca, Sunda Strait, and Lombok Strait, China has struck extensive infrastructure deals with Indonesia and Myanmar. The Kyaukpyu Port in Myanmar provides another alternative route bypassing the Malacca chokepoint. In Sri Lanka, China’s Hambantota Port—seized after debt defaults sits astride critical shipping lanes south of India.

China has also partnered with Mozambique and gained influence over Tanzania’s Dar es Salaam Port. Through these systematic investments, China is literally encircling India while asserting influence over regions critical to global trade.

The Indian Ocean’s Hidden Wealth: Resources Beyond Oil

While chokepoint control drives the India-China Indian Ocean competition, the ocean’s resource wealth adds another dimension. Approximately 16.8% of global oil reserves and 27.9% of natural gas reserves lie within this region—much of it still unexplored.

China’s increasing trade relations underscore long-term resource ambitions. As of 2017, China accounted for 16.1% of total goods trade in the Indian Ocean Region. Infrastructure projects in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Djibouti all align perfectly with China’s oil import and export routes to Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

This systematic approach—combining chokepoint control, resource access, and trade dominance—defines the String of Pearls China in its entirety.

The Necklace of Diamonds: India’s Silent Counter-Strategy

To counter strategic encirclement, India has quietly initiated the Necklace of Diamonds strategy. Unlike China’s debt-trap infrastructure model, India’s approach emphasizes partnerships, military access agreements, and strategic port development.

India has tactically positioned itself near China’s strongholds. At Gwadar and Djibouti, India partnered with Oman for access to the Port of Duqm. This facility on the Arabian Sea provides India with crucial positioning for Persian Gulf crude oil imports while monitoring Chinese activities at nearby Gwadar.

The Necklace of Diamonds doesn’t seek to match Chinese spending dollar-for-dollar. Instead, it leverages India’s democratic values, historical ties, and mutual security interests to build sustainable partnerships across the Indian Ocean.

Strategic Partnerships Across Critical Waters

At the Mozambique Channel, India signed a 2015 agreement with Seychelles to develop Assumption Island for military use. Though facing political hurdles and local protests, this move signals India’s determination to assert its presence in key trade corridors.

Given the Strait of Malacca’s importance, India secured access to Singapore’s Changi Naval Base. This allows Indian Navy vessels to refuel and rearm while transiting the South China Sea. Additionally, India partnered with Indonesia for access to Sabang Port, strategically positioned at the Malacca Strait’s western entrance.

These arrangements don’t transfer sovereignty or create debt dependencies. They establish mutual defense cooperation benefiting all parties—a stark contrast to the String of Pearls China debt-trap model.

India’s Eastern Partnerships: Japan and Vietnam

Further east, the Necklace of Diamonds extends to Vietnam and Japan. On September 9, 2020, India and Japan signed the Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA), enabling both militaries to exchange supplies and services reciprocally.

This agreement allows Indian vessels to access Japanese ports for maintenance and resupply throughout the Pacific. Similarly, Indian Air Force aircraft can now operate from Japanese bases during joint exercises or contingencies. Such arrangements multiply India’s power projection capabilities without massive infrastructure investments.

In Mongolia, Prime Minister Modi became the first Indian leader to visit, leading to agreements for bilateral air corridor development backed by Indian credit lines. These partnerships surround China from multiple directions, creating strategic depth for India.

Chabahar Port: India’s Masterstroke Against Gwadar

India’s development of Chabahar Port in Iran represents perhaps the most brilliant move in the Necklace of Diamonds strategy. In 2015, when Iran faced crippling economic sanctions and diplomatic isolation, India committed $500 million to develop this deep-water port and related infrastructure.

Located on the Gulf of Oman, Chabahar lies just 72 kilometers from the Chinese-controlled Gwadar Port in Pakistan. This proximity provides India with direct strategic leverage. While China uses Gwadar to access the Arabian Sea, India uses Chabahar to monitor Chinese activities and maintain alternative access to Central Asia.

Chabahar also bypasses Pakistan entirely for Indian trade with Afghanistan, Iran, and the Central Asian republics. This overland route reduces dependence on vulnerable sea lanes while strengthening economic ties with resource-rich regions. The port became operational in 2017 and continues expanding.

Beyond Infrastructure: A Battle of Governance Models

The Necklace of Diamonds versus the String of Pearls: China represents more than maritime competition. It’s a contest between governance models. China’s approach creates debt dependencies, transfers sovereignty, and prioritizes Chinese interests. Several nations now struggle with unsustainable Chinese loans.

India’s partnerships emphasize mutual benefit, democratic values, and respect for sovereignty. This approach builds more slowly but creates more sustainable alliances. As nations like Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Myanmar experience Chinese debt burdens, India’s model becomes increasingly attractive.

The Resource Competition: Oil, Gas, and Minerals

While both the String of Pearls and Necklace of Diamonds focus on maritime control, they’re ultimately competing for resources. The Indian Ocean contains vast untapped oil and gas reserves. Whoever controls the sea lanes controls access to these resources.

China’s energy security depends entirely on imported oil. Over 80% of Chinese oil imports transit the Indian Ocean, particularly through the Strait of Malacca. This “Malacca Dilemma” drives Chinese efforts to secure alternative routes via Myanmar and Pakistan.

India faces similar dependencies but with geographic advantages. Positioned centrally in the Indian Ocean, India enjoys shorter supply lines and natural defensive positions. The Necklace of Diamonds leverages these advantages to secure energy supplies while denying China unfettered access.

Future Flashpoints: Where Competition May Turn Confrontational

Several locations may see intensified India-China Indian Ocean competition. The Maldives, with its strategic position astride major shipping lanes, faces constant pressure from both powers. Recent political changes have swung the nation between pro-China and pro-India governments.

Bangladesh represents another contested space. Chinese investment in Chittagong Port and infrastructure threatens to pull Bangladesh into Beijing’s orbit. India counters with development assistance and defense cooperation, but economic realities favor China’s deeper pockets.

Myanmar’s Kyaukpyu Port development illustrates these tensions perfectly. Initially, a massive Chinese project, Myanmar scaled back plans after recognizing debt-trap risks. India now competes for influence through the Kaladan Multimodal Transit Transport Project.

The American Factor: QUAD and Indo-Pacific Strategy

The India-China Indian Ocean rivalry doesn’t occur in isolation. The United States, through the QUAD alliance (USA, India, Japan, Australia), actively supports India’s Necklace of Diamonds. This partnership provides India access to advanced military technology, intelligence sharing, and diplomatic backing.

The QUAD’s “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” vision directly contradicts the String of Pearls China encirclement strategy. Joint naval exercises, technology transfers, and coordinated infrastructure development strengthen India’s position significantly.

However, India maintains strategic autonomy. Unlike treaty allies, India preserves relationships with Russia and Iran while cooperating with the West. This multi-alignment approach maximizes India’s options while avoiding dependency on any single power.

Economic Implications: Trade Routes and Regional Development

Beyond military posturing, both strategies profoundly impact regional economic development. The String of Pearls China creates new trade corridors, reducing dependence on traditional Western-controlled routes. For participating nations, this brings infrastructure development and economic opportunities.

Yet these benefits come with strings attached. Chinese loans carry high interest rates, use Chinese contractors, and often transfer port management to Chinese companies. Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port handover after debt default illustrates these risks clearly.

The Necklace of Diamonds offers slower but more sustainable development. Indian investments emphasize capacity building, technology transfer, and local employment. While less spectacular than Chinese mega-projects, they create more balanced partnerships.

Conclusion: The Century-Long Contest for Ocean Dominance

The String of Pearls China versus Necklace of Diamonds represents the defining geopolitical contest of the 21st century. As China’s encirclement tightens around the Indian Ocean, India’s counter-strategy emerges as robust, calculated, and geographically comprehensive.

Through naval bases, strategic partnerships, and critical port developments, India safeguards national interests while maintaining a balance of power in the Indo-Pacific. The Necklace of Diamonds may lack the spectacle of Chinese mega-projects, but it builds sustainable alliances based on mutual respect and shared interests.

The unfolding dynamics of this maritime rivalry will determine not just South Asian security architecture, but the broader geopolitical future of our century. Control of the Indian Ocean means control of global trade, energy security, and ultimately, economic prosperity for billions of people.

As these strategies evolve, one truth remains constant: the nation that masters the Indian Ocean will shape the Asian century. Whether that’s China through the String of Pearls or India through the Necklace of Diamonds remains the great strategic question of our time.