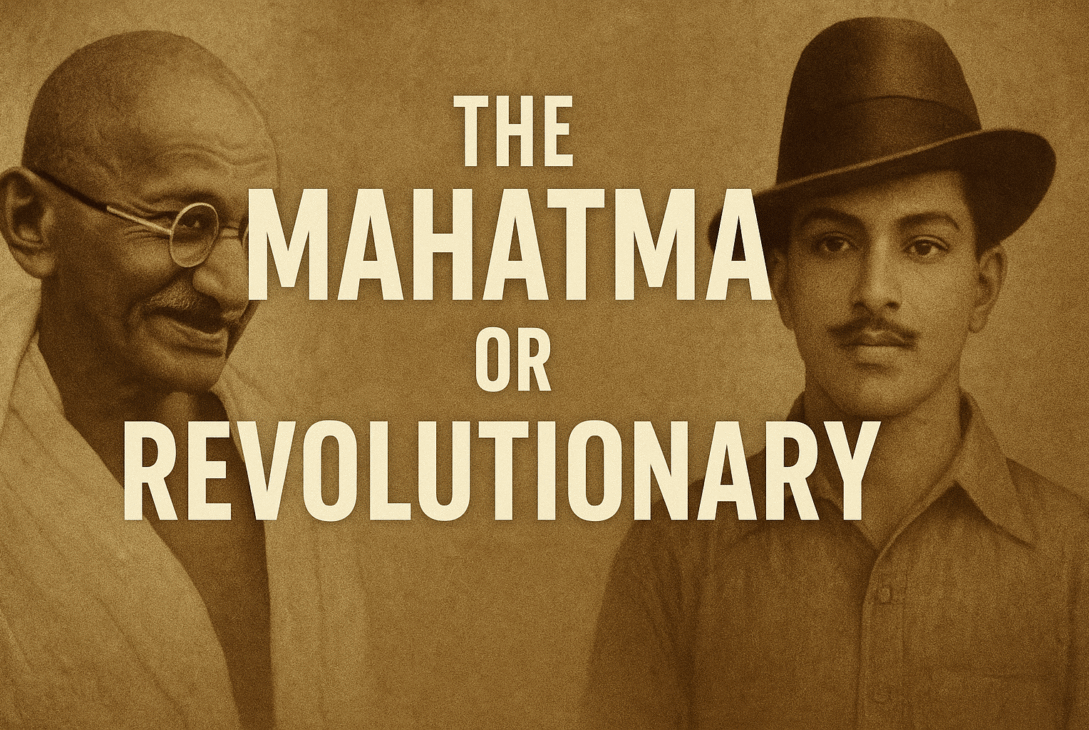

Was India’s freedom won solely by non-violence — or forged in the fire of revolutionary sacrifice?

Picture two scenes: Mahatma Gandhi leading a peaceful march with spinning wheel in hand, and Bhagat Singh hurling a bomb in the Central Legislative Assembly, shouting “Inquilab Zindabad!” Both men fought for the same dream — an independent India — yet their methods, worldviews, and moral universes stood poles apart. The sanitized versions we learn in classrooms blur this contrast, reducing one to a saint and the other to a martyr. But the truth is far more complex, and far more human.

The Architect of Satyagraha: Gandhi’s Battles Within and Without

Mahatma Gandhi, the moral architect of India’s freedom, was also a man perpetually at war with himself — over flesh, faith, race, caste, and economy. His greatness lay not in perfection, but in his constant struggle with his own contradictions.

The Brahmacharya Experiments

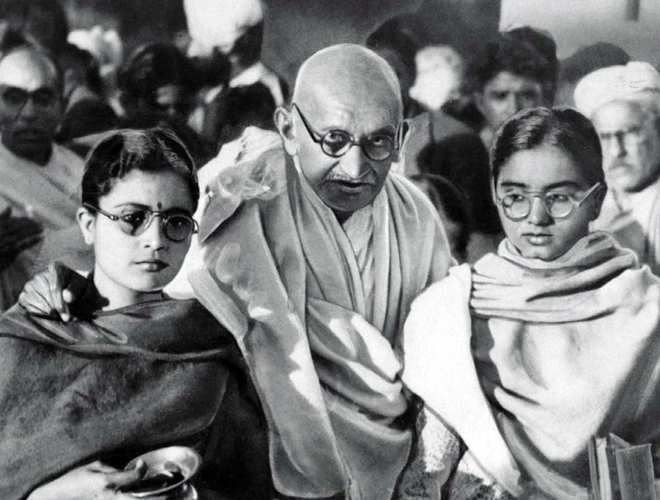

Few aspects of Gandhi’s life are as controversial as his brahmacharya or celibacy tests. In 1946, Gandhi slept beside young women — including his grandnieces Manu and Abha, and his personal doctor, Sushila Nair — to test his self-control. He claimed it was an experiment in conquering desire and purifying the soul, believing that sexual restraint would help quell the communal violence ravaging India

Even close associates were horrified. Many saw it as moral delusion rather than discipline. Gandhi’s rationale stemmed from a deep psychological scar — the guilt he carried from his youth, when his father died as Gandhi lay with his wife. Ever since, he equated sex with sin and self-indulgence. He opposed contraceptives and birth control, arguing they encouraged moral weakness. To him, chastity was power — but to others, it was repression masquerading as virtue.

The Shadow of Racism

Before becoming the “Mahatma,” Gandhi spent two decades in South Africa — a crucible that shaped his political philosophy but also exposed his early prejudices. His writings from that era reveal unsettling attitudes: describing Black Africans as “Kaffirs,” “uncivilized,” and “lazy,” and demanding that Indians not be “classed with the natives.” He urged British authorities to grant Indians higher status, claiming both races were “Indo-Aryans” and therefore superior to Africans.

Though later defenders insist his views evolved, African scholars argue his racial hierarchy persisted well into his forties. It’s why his statue was removed from Ghana University in 2018 — a reminder that even prophets of equality can bear the stains of their times.

The Caste Conundrum

Gandhi’s relationship with India’s caste system was one of moral evolution — but also deep contradiction. He fought untouchability and called the oppressed “Harijans,” yet defended the varna order as a “natural division of labour.” In his early writings, he even called the caste system essential to Hindu society’s strength.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar accused him of “playing a double game” — one face for English audiences demanding reform, another for Indian followers defending tradition. Their clash culminated in the 1932 Poona Pact: Ambedkar demanded separate electorates for Dalits; Gandhi fasted unto death to prevent it. The compromise reserved seats but denied Dalits political independence.

Gandhi’s idea of the “Ideal Bhangi” — a sanitation worker devoted to his duty — showed both compassion and condescension. Only in the late 1930s did he write that caste “must go.” But which Gandhi do we remember — the reformer or the rationalizer of inequality?

The Economics of Self-Reliance

Gandhi’s economic thought, rooted in Swadeshi and Sarvodaya, rejected industrialism and capitalism alike. He envisioned a nation of self-sufficient village republics, spinning their own cloth and consuming what they produced. His trusteeship model urged the rich to act as custodians of wealth for society’s good — a spiritual antidote to greed.

Critics like Ambedkar and Nehru found it utopian, arguing that it would trap India in pastoral poverty. Yet modern environmentalists hail it as a precursor to the “circular economy,” where waste becomes resource and sustainability trumps profit. Gandhi’s economics, like his ethics, straddled idealism and impracticality — visionary, but detached from industrial reality.

The Spark of Inquilab: Bhagat Singh’s Revolutionary Sacrifice

If Gandhi’s strength lay in moral persuasion, Bhagat Singh’s power came from intellectual rebellion. He was not merely a bomber or a martyr — he was a philosopher of revolution.

From Non-Cooperation to Armed Revolution

Bhagat Singh began as a follower of Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation Movement, but the 1922 Chauri Chaura incident — where Gandhi suspended the campaign after a violent riot — left him disillusioned. The massacre at Jallianwala Bagh, which he witnessed as a 12-year-old, had already filled him with rage and purpose.

He realized that freedom could not be begged for; it had to be seized. He joined the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) and, with comrades like Chandrashekhar Azad and Sukhdev, dedicated himself to a revolutionary path.

More Than a Bomb: The Intellectual Revolutionary

To reduce Bhagat Singh to a gun-toting insurgent is to miss his genius. He was an articulate writer, founding the Naujawan Bharat Sabha to unite youth across religion. He published essays in Kirti magazine, organized hunger strikes for prisoners’ rights, and used his trial as a stage for ideological warfare.

In the Assembly Bombing of 1929, he and Batukeshwar Dutt threw non-lethal bombs and shouted “Inquilab Zindabad!” — not to kill, but “to make the deaf hear.” They courted arrest, turning their courtroom into a classroom of revolution. His defense speech remains one of the most brilliant political manifestos in Indian history.

“Why I Am an Atheist”

In jail, Bhagat Singh wrote his legendary essay Why I Am an Atheist. He rejected religion not out of arrogance but out of reason. “If God is just and merciful,” he asked, “why does he allow injustice and poverty to thrive?” He saw blind faith as a tool of oppression, used by priests and politicians alike.

His atheism was not nihilism — it was moral independence. He believed the divine was not in temples but in human conscience and courage. Even on the eve of his execution, when asked to pray, he refused, saying he would not seek God’s mercy now if he hadn’t believed in Him all his life.

The Strategic Sacrifice

The killing of British officer John Saunders in 1928 — a mistaken target meant to avenge Lala Lajpat Rai’s death — revealed both the precision and peril of revolutionary action. The subsequent Assembly bombing was deliberately symbolic. Bhagat Singh wanted his trial to awaken a nation, not terrorize it.

During the Lahore Conspiracy Case, he turned the courtroom into a pulpit for equality, workers’ rights, and freedom. His hunger strike for political prisoners’ dignity inspired mass uprisings. When sentenced to death at 23, he wrote calmly to his mother: “The struggle will continue, and victory shall be ours.”

The Irreconcilable Gulf: Non-Violence vs. Revolution

Between Gandhi’s spinning wheel and Bhagat Singh’s pistol lay a gulf that defined India’s liberation story. Gandhi believed that violence degrades both oppressor and oppressed; Bhagat Singh believed that violence, when directed at tyranny, could awaken a slumbering nation.

Gandhi once called revolutionaries “cowards” for resorting to bloodshed. Bhagat Singh, in turn, saw non-violence as moral luxury — a privilege the oppressed couldn’t always afford.

Yet, history’s irony lies in their intersection. When Bhagat Singh awaited execution in 1931, Gandhi appealed to Viceroy Irwin to commute his sentence — but refused to publicly glorify his methods. The pleas failed. On March 23, 1931, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru were hanged in Lahore Jail — chanting “Inquilab Zindabad!”

The two men never met, but their destinies intertwined. Gandhi’s moral force softened British resolve; Bhagat Singh’s defiance hardened Indian will.

Conclusion: Beyond Devotion and Demons

To pit Gandhi and Bhagat Singh against each other is to misunderstand both. Gandhi wrestled with his inner demons — lust, guilt, and moral contradiction — to redeem society through soul-force. Bhagat Singh fought external demons — injustice, superstition, and imperial power — through intellect and sacrifice.

One sought redemption through suffering; the other through resistance. One preached evolution, the other demanded revolution. Yet, both expanded the moral and political imagination of a colonized nation.

India’s freedom was not a single-note symphony of non-violence — it was a duet of conscience and courage. The British quit India because they feared both Gandhi’s moral disobedience and Bhagat Singh’s armed defiance.